How was it built: the iconic Forth Bridge

Conservation, History, Industrial Heritage, Maintenance | Written by: Miles Oglethorpe | Tuesday 18 April 2023

The Forth Bridge is one of the engineering wonders of the world. It became an international tourist attraction, even when it was being built. Find out more about how this incredible structure was built and what the conservation challenges are today.

A revolution in steel

A train crossing the Forth Bridge © HES

The origins of the Forth Bridge’s distinctive ‘cantilever’ design lie in one of the biggest civil engineering disasters in history – the collapse of first Tay Bridge in 1879. This caused its designer, Sir Tomas Bouch, to lose the contract he had won for the Forth Bridge, and for much more rigid and robust alternative designs to be proposed.

John Fowler and Benjamin Baker’s iconic cantilever design eventually won the competition, but by the time construction began in 1882, the world had changed and civil engineering was able to use a revolutionary new material: mild steel.

The mass production of steel was revolutionised by the Bessemer Process in the 1850s, but production costs and quality-control issues caused by impurities in iron ore hindered its advance.

These problems were overcome by the open-hearth furnaces of the Siemens Martin Process from the 1870s. The Forth Bridge provided the perfect opportunity to prove the enormous potential of this revolutionary, affordable new material.

Building the bridge

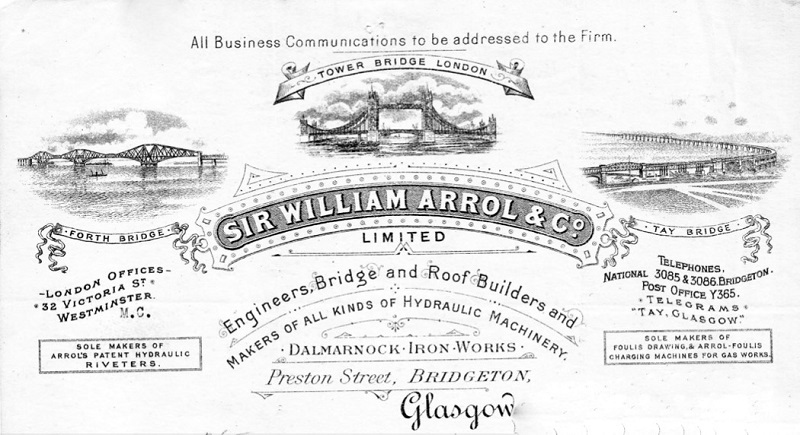

A letterhead dating from around 1930 showing three flagship Arrol projects: The Forth Bridge, Tower Bridge in London, and the rebuilding of the Tay Bridge. © HES, The Arrol Collection.

The job of actually building the Bridge fell to William Arrol, a Glasgow engineering company that went on to build other iconic structures across the world, including the adjacent Forth Road Bridge, the replacement Tay Bridge, Tower Bridge in London and the giant cranes of the Clyde.

Given its enormous scale, building the Forth Bridge was an immense logistical operation, and Arrol was able to deploy emerging technologies such as hydraulic power to support the project.

Eight years of construction

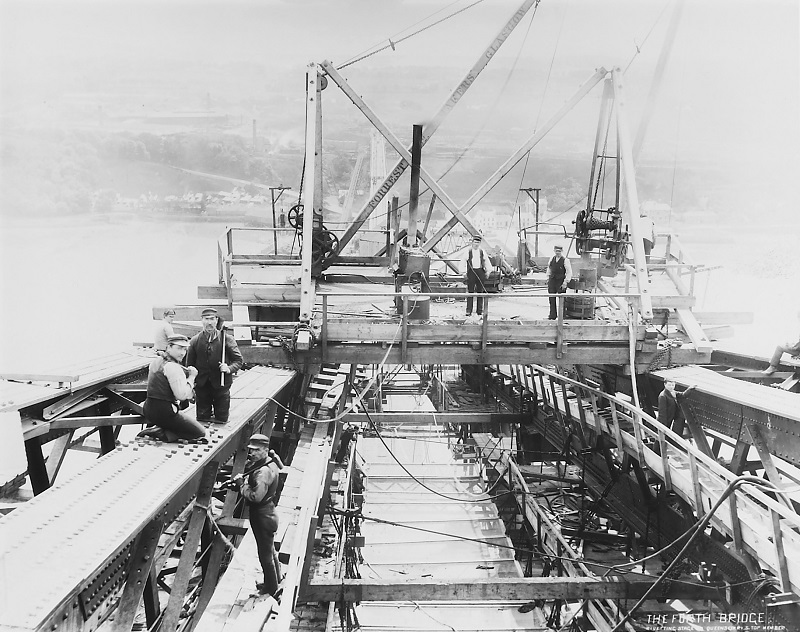

Evelyn Carey’s progress photographs documenting the construction of the Forth Bridge. In the centre left of this image, taken in 1889 on top of the Bridge’s Queensferry Tower, you can see riveters removing the temporary nuts and bolts and replacing them with permanent rivets. You can also see North Queensferry in the background. Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, BR/FOR/4/34/51

The construction took eight years, concluding with the opening ceremony on 4th March 1890. From start to finish, this process was recorded in great detail by engineer photographer, Evelyn Carey. His original glass plates are in the safe care of the National Records of Scotland and have been digitised so that they can be shared with the world.

Arrol established what was, in effect, a large factory and yard adjacent to the bridge where mild steel plate was brought from factories in Wales, England and Scotland.

Once there, it was cut and bent into shape and then pre-assembled to check all the component parts were present and correct. This was seven decades before the welding of steel became established practice, so all the steel plates had to be riveted. This involved drilling holes along their edges and then tying them together with rivets.

So, the bridge was in effect built twice. First, the component elements were assembled in the factory below, and then for real on the bridge itself. On each occasion, nuts and bolts were initially used to join and hold steel plates together, but once everything was properly in place, these were removed and permanent hot rivets were inserted and hammered home by riveters and hydraulic riveting machines that had been designed by Arrol himself. It is estimated that, on its completion, the bridge contained over 50,000 tonnes of mild steel and at least 6.5 million rivets.

Working on the bridge

The story of the construction of the Forth Bridge was recorded in great detail by the engineer Wilhelm Westhofen and published in 1890 in the journal, Engineering. Since then, many people have published books and articles, but one of the most important bodies of research has been by the local history group, The Briggers, based in Queensferry.

They have explored what it must have been like to have worked on the bridge and have researched the names and details of all those who worked and died both during and after its construction, some of whom were only boys as young as 12 years old. In total, they estimate that at least 73 people died directly as a result of working on the bridge between 1882 and 1890, and their names have been immortalised in memorials erected in both Queensferry and North Queensferry.

While the bridge was being built, Lady Margaret Moir, who frequently visited the bridge’s caisson foundations, became greatly concerned about how pressure from giant cylinders on the river bed caused a painful and dehabilitating condition. Her husband, Ernest Moir, was a rising star in the civil engineering profession, who was responsible for building one of the bridge’s great cantilevers. Encouraged by Margaret, Ernest went onto develop the world’s first Medical Air Lock to relieve the condition caused by the effects of compressed air.

A conservation challenge

There can be few greater conservation challenges in the world of industrial heritage than that of mild steel. This is because there’s so much of it out there, and a lot of it is on a grand scale, sometimes forming prominent, iconic parts of familiar landscapes.

As we have seen, one of the most obvious and early examples is the Forth Bridge. Twenty years ago, the condition of the bridge aroused great political and media interest. The result of this attention was an enormously ambitious restoration scheme costing approximately £140 million. It took over a decade to complete. In the process, the bridge was covered in patches of scaffolding and white plastic encapsulation. This allowed the layers of original paint, which contained red lead, to be stripped off safely and replaced with a new epoxy-based three-layer coating system developed for the offshore marine environment.

Painting the Forth Bridge

© View from the base of the Queensferry tower in 2011 showing the paint mixing station and temporary scaffolding being erected to enclose the paint removal and recoating processes (Miles Oglethorpe 2011)

At the time the Forth Bridge was built, the paint was supplied by Edinburgh manufacturer Craig & Rose. It was a distinctive red colour.

In subsequent years, the task of painting the Forth Bridge was immortalised because it was seen to be a never-ending, continuous process. If someone had what seemed to be an endless task, it was often said to be ‘…like painting the Forth Bridge’. People will probably continue to use this phrase for years to come, but in truth, this is no longer the case at the bridge because of the introduction of the new coating system by Network Rail and their contractors, Balfour Beatty!

Whilst the old system tended to involve painting over old layers of paint, the restoration project required all surfaces to the stripped back to bare steel. This was an enormous operation, and in order to stop the original lead paint falling into the Firth of Forth below and finding its way into fish suppers in Anstruther, areas of work where grit blasting was occurring were encapsulated inside scaffolding and plastic sheeting. Within these ugly white boxes were giant industrial vacuum cleaners which were deployed to hoover up all the paint and grit before the new coatings were applied.

Restoration

© View from near the top of the Queensferry tower in 2011 showing the repainting process nearing completion (Miles Oglethorpe 2011)

I visited the bridge in 2011, only a year before the completion of the restoration project. It was extraordinary to see the scale and complexity of the works in progress, and the astonishing skills of the scaffolders who were often exposed to challenging weather conditions. When the job was completed in 2012, the bridge probably looked better than it ever had, even shortly after it was opened in 1890. The timing could not have been better as it helped support the Forth Bridge’s successful nomination for World Heritage listing in 2015.

In the meantime, the restoration project deservedly won many awards, and the current maintenance programme is now overseen by much smaller team. The expectation is that the new paint system will not require renewal for another 20-30 years.

About the author:

Miles Oglethorpe

Miles Oglethorpe was Head of Industrial Heritage at Historic Environment Scotland, and has been involved with the Forth Bridge since just prior to its centenary in 1990. Miles is currently President of TICCIH, the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage.

View all posts by Miles Oglethorpe