The Tay Bridge Disaster: A Lesson in Design and Maintenance

Maintenance, Materials | Written by: Sophie McDonald | Wednesday 11 January 2017

While Scotland has been home to some great writers like Robbie Burns and Sir Walter Scott, we’ve also produced some who were… less talented!

Many people would say that William McGonagall falls into the second category. He’s widely regarded as Scotland’s worst poet, although he’s also been described as being “so giftedly bad, he backed into genius”.

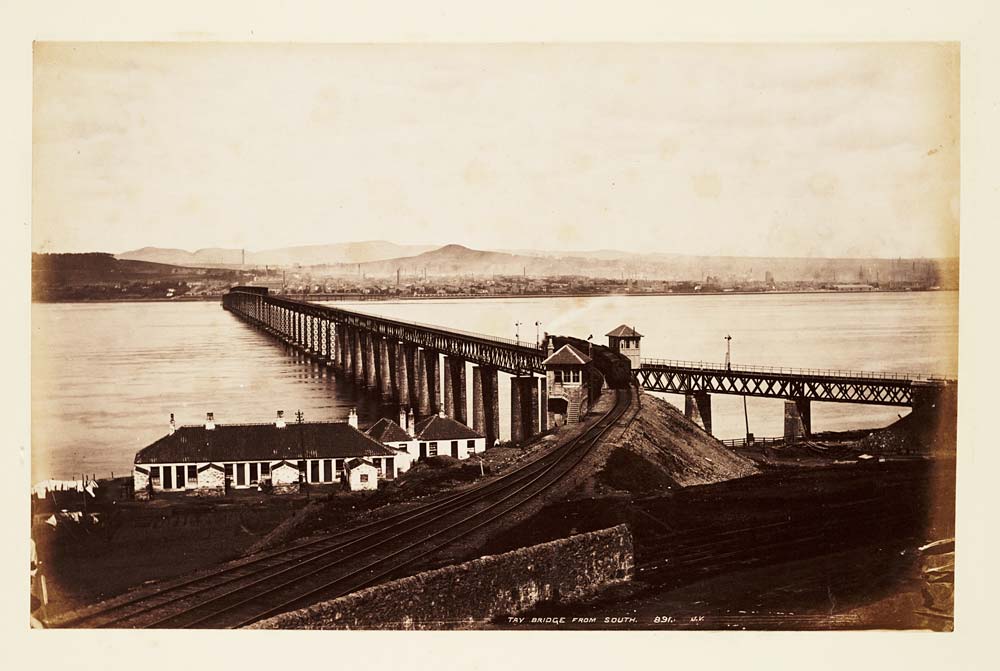

The Tay Bridge before its collapse (National Library of Scotland).

McGonagall’s links to the Tay Bridge Disaster

So what is the link between McGonagall and conservation? He’s most famous for his poem about the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879. On 28 December of that year, the bridge collapsed during a severe gale. A train had been passing over it at the time, and 75 people were killed as it plunged into the river’s icy waters.

Only two years earlier McGonagall had written a poem praising the bridge for its “numerous arches and pillars in so grand array”. The poem went on to declare that the bridge was “A great beautification to the River Tay”. However, after the disaster he criticised the way that the bridge had been built:

“Oh! ill-fated Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay,

I must now conclude my lay

By telling the world fearlessly without the least dismay,

That your central girders would not have given way,

At least many sensible men do say,

Had they been supported on each side with buttresses,

At least many sensible men confesses,

For the stronger we our houses do build,

The less chance we have of being killed.”

A flawed design

William appears to have been right about why the bridge collapsed. Its narrow width and top-heavy “high girders” and piers had given way in winds of up to 80 miles an hour. They fell into the Tay, taking the train with them.

Part of this was because of flaws in its design, but poor maintenance was also an issue. Cracked sections of the bridge’s columns had been filled with beeswax and iron filings, and parts of the ironwork had loosened at “lugs”. The investigation into the disaster concluded that the bridge’s poor design and maintenance had been major reasons why it failed.

The Tay Bridge after its collapse (National Library of Scotland).

Sir Thomas Bouch, who had designed the bridge, was disgraced. He had produced designs for the Forth Bridge but after this catastrophe, they couldn’t be used.

Maintaining ironwork

Although the results of damage or corrosion might not always be as catastrophic as the Tay Bridge Disaster, ironwork in traditional buildings needs to be inspected regularly to check for signs of damage or corrosion.

Iron is generally a durable material, but regular inspections and maintenance are still required to help prevent decay. When iron comes into contact with air and water for prolonged periods, it reacts to form iron oxide, which we see as rust.

This flakes off from the surface of the iron, which can compromise the integrity of a structure. Iron in traditional buildings can be protected from corrosion by regular painting to keep the metal dry. This prevents corrosion occurring.

Tips for repairing ironwork

If you do find corroded ironwork in a traditional building, repairs may be necessary. We recommend that any repairs or replacements be kept to a minimum, and use high-quality materials and techniques. As much of the original ironwork as possible should be kept.

Even the replacement Tay Bridge contains all of the undamaged girders that were recovered after the Tay Bridge Disaster, incorporated into a safe, sturdy design. The bridge, opened in 1887, is a listed building. It’s maintained by Network Rail.

Check out our website for more advice and publications on how to look after iron in traditional buildings and structures.

About the author:

Sophie McDonald

Sophie worked as a Digital Content Officer with Historic Environment Scotland until 2017, spending her time looking after the Engine Shed's blog posts and social media channels.

View all posts by Sophie McDonald