Preserving trades across the pond: our top 6 takeaways from the International Preservation Trades Workshop

Behind the Scenes, Conservation, Skills | Written by: Guest | Thursday 5 December 2024

Cat Hotchkiss, HES Vernacular Buildings Craft Fellow, based at the Scottish Crannog Centre. She is pictured here in one of its roundhouses during construction.

What can we learn from building conservation practices in the USA, and what can they learn from our practices in Scotland? Our Craft Fellows Cat Hotchkiss and Gordon Muir went along to the International Preservation Trades Workshop (IPTW) to find out.

Each year, at the IPTW, the Preservation Trades Network (PTN) brings new entrants and in-training craft people together with experienced craft practitioners. The event is hosted in a different location each year. We even hosted the IPTW here at the Engine Shed in 2019!

This year’s IPTW was held in Savannah, Georgia, the state’s oldest city, and was hosted by Re: Purpose Savannah. Our first interactions with this skilful community began as we mucked in with the set-up at their base, a women-led nonprofit ‘establishing a sustainable future through the deconstruction, salvage, and reuse of historic buildings’ and who aim to ‘train women+, including women-identified, trans, non-binary, and other underrepresented people, for careers in construction’.

Read on to discover our top six takeways from the demonstrations, talks and networking. Learn why it’s important to transcend borders to help traditional building skills thrive.

Traditional wooden windows, with timings and activities for the day written on the glass. © Cat Hotchkiss

1. You can do incredible things with a few hand tools

Innes giving a stonemasonry demonstration.

Our Craft Skills Training Officer and stonemason, Innes Drummond, who led our small team to the IPTW in Savannah, demonstrated what you can do with a hammer, mallet and a few chisels with ‘The Art of Perseverance: the Challenges a Stonemason Faces’. In an age focused on machinery and technology, the art of perseverance helps you to realise what’s possible when working on a building in the middle of nowhere. He explained how to get familiar with stone you have never worked before and how it reacts to being struck by hand tools. Stonemasonry provides key skills like problem-solving when things don’t go to plan, such as turning a random block of stone into an architectural feature or into something useful featuring Greek and Roman profiles.

2. We have similar approaches to working with stained glass in Scotland and the States

The two stained glass demonstrators at the IPTW worked in harmony. First was ‘Shimmering beginnings: stained glass journey’ with Melanie Hendrix and second was ‘Is your stained glass crying for help?’ with Rhonda Deeg. Melanie Hendrix provided a broad view into the craft and Rhonda Deeg, owner of RLD Glass Art & Restoration, Indiana gave a generous account of everything she could impart from her many years repairing historic windows.

The similarities in approach, techniques and care that Rhonda takes with her projects was comforting. Like Rob MacInnes’ glass studio in Glasgow (Gordon’s Stained Glass Craft Fellowship host), Rhonda’s studio is in part of her house, and the same precautions must be taken regarding health and safety.

Left: Rab MacInnes (Gordon’s Stained Glass Craft Fellowship host) working in his studio in Glasgow. Right: Gordon Muir, Stained Glass Craft Fellow in the same studio.

In terms of conserving and repairing stained glass in the U.S., funding can be challenging. Places of worship tend to raise funds through their wide network of congregations, and Rhonda explained how she often will do work in stages to suit client’s funding streams. She has also carried out work at lower financial estimates because she sees the intrinsic value of the glass and its preservation is an essential part of her heritage.

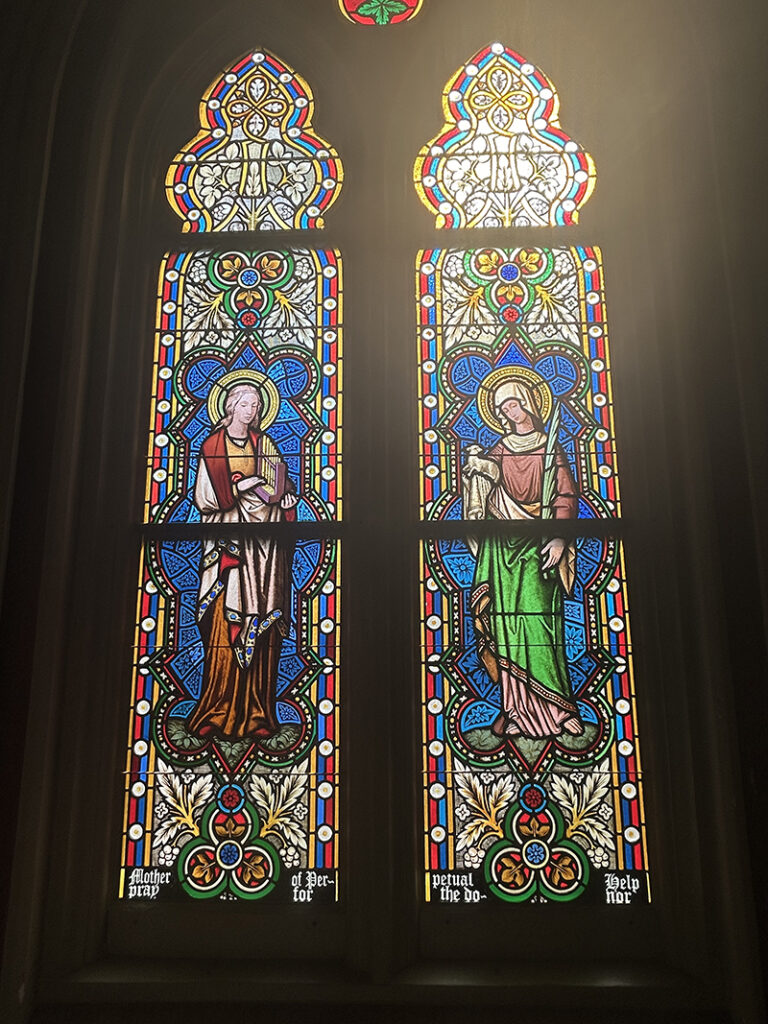

3. Savannah’s stained glass has Celtic connections

We contacted the Savannah Cathedral office and arranged to meet a Docent there to learn about its stained-glass windows, all crafted by the Tyrolean Glassworks of Innsbruck. The Docent, Peter Paolucci, provided records of the pricing of glass replacements after the Cathedral’s fire in 1898. Peter also allowed us access to photograph the two surviving original windows.

The two surviving windows from the Savannah Cathedral fire in 1898. St Cecilia and St Agnes are depicted. © Gordon Muir.

On a visit to Savannah Congregation Mickve Israel Synagogue, built in 1876, we discovered magnificent windows by William Gibson’s Sons of New York, installed the same year. A highlight was discovering links and friendship with the Hibernian Society of Savannah, which remains active today. This friendship is recorded in the stained glass located in internal doors in the Synagogue, with Celtic knotwork and images of harps.

Congregation Mickve Israel synagogue-stained glass © Gordon Muir.

4. Timber is considered sustainable in the States

Timber framers Mike Goldberg and Stephen Morrison (representing the Timber Framers Guild and MoreSun) demonstrated their methods for processing and preparing lumber for bespoke structures, culminating in the raising of a bent – the timber goal post structure which becomes the main load-bearing assembly of a milled timber frame. They shared their tips (a mirror with a hole in it for straight pilot holes!) and discussed the divergences from the UK vernacular.

Douglas fir, a durable native softwood favoured in the USA, only arrived in Scotland in 1829. Now popular in our vernacular buildings, the climactic variations and forestry approaches means it’s still a different lumber from the material worked by our USA counterparts. Southern Yellow Pine is also a standard in the south-easterly states.

‘Raising the bent’ with Mike Goldberg © Cat Hotchkiss.

In the States, there’s a rich tradition of timber construction, which continues to this day. This is in part due to the wide availability of suitable lumber which can be sourced locally and cost-effectively. The tradition is supported by the Timber Framers Guild (TFG) serving as an information center for the broad community of craft workers and their educational arm known as Heartwood School. The Guild leads a community build once a year, sharing skills, pulling the community of timber workers together and enabling their chosen not-for-profit organisation to construct a beautiful timber frame structure for the cost of materials.

5. Make sure you explore opportunities with experts

A colourful and ornate Victorian mansion surrounding Forsyth Park © Cat Hotchkiss.

Having also sparked a conversation with Connie Pinkerton, Head of the Historic Preservation Department at Savannah Technical College, Gordon arranged to present a talk and workshop on stained glass at the college. The talk was illustrated with images of the recent commission for The Red Forest windows in Websters Theatre, Glasgow, amongst other images of the processes and materials used in stained glass practice. The students were also introduced to the work of Alf Webster, and Scottish stained-glass history dating back to the 11th century.

The workshop allowed students the opportunity to stretch and cut lead, cut small pieces of glass, and use the soldering iron to make lead joints.

Gordon Muir (centre) leading a stained glass workshop to Savannah Technical College Students © Connie Pinkerton.

6. Salvaging can help to record details of a building

Mae Bowley, Keynote Speaker and previous Executive Director at Re:Purpose drew a compelling argument for the deconstruction of buildings to be understood as a preservation craft in its own right.

Following the etymology of a ‘wrecking crew’, those who salvage material from shipwrecks, Bowley suggests that demolition does not necessitate the end for buildings and materials, but the historic and material continuation of their life. Their social histories can be recorded, the structure and materials carefully documented, and then deconstructed, salvaged and repurposed. Some of the wood stacked in the Re:Purpose yard was from virgin forests, felled for Savannah’s British colonial homes.

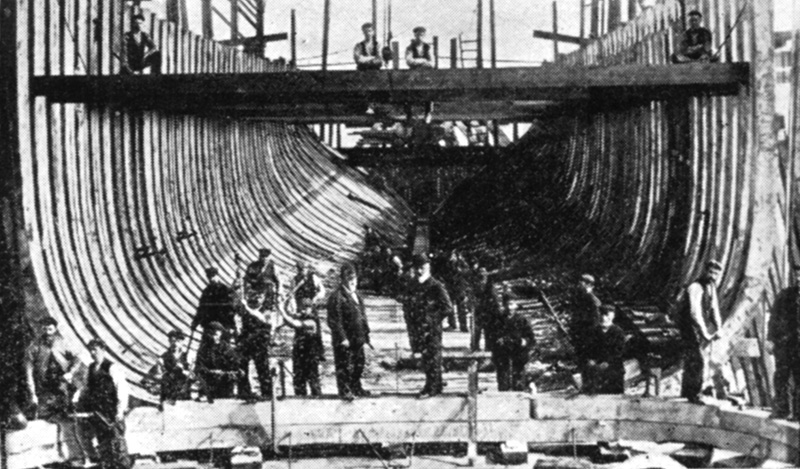

This struck a chord with Cat following her work on the Royal Research Ship Discovery in Dundee, repairing the stern of the ship. Huge oak posts reclaimed from a sunken warship in the Irish Sea are being used for the repair, providing an age-appropriate replacement for the historically significant timbers.

Right: Building the RRS Discovery, circa 1900. © Douglas MacKenzie. Licensor: www.scran.ac.uk.

In these times of climate change and our transition to net zero, it feels as important to honor the history of our materials through reuse with our traditional craft skills, as it does the architectural heritage of the country.

Find out more

It was a thought-provoking experience, with so many examples of traditional building skills on display. Discover more about the Preservation Trade Network (PTN) who run this event annually. To find out more about Cat’s work at the Scottish Crannog Centre, read our blog Discover four key traditional building skills at the Scottish Crannog Centre’s Iron Age Village. To delve deeper into Gordon’s work in stained glass, read Creating the Red Forest: a Gaelic stained glass commission in Glasgow.

About the authors:

Cat Hotchkiss is a Vernacular Buildings Craft Fellow, part of our Trainee and Craft Fellowship Programme, based at the Engine Shed and hosted by the Scottish Crannog Centre, a living history museum on Loch Tay. Cat has a background in visual art, community libraries and skill sharing, with experience in carpentry and sustainable building practices. Her craft fellowship supports the retention of traditional building skills with vernacular materials and involves working on an interpretation Iron Age village and Crannog in the Scottish Highlands

Gordon Muir is a Stained Glass Craft Fellow, part of our Trainee and Craft Fellowship Programme, based at the Engine Shed and hosted by ICON accredited stained glass specialist Rab MacInnes. Gordon has a background in Fine Art Painting, Community Arts, and social care with experience in conserving and creating stained glass windows. His Craft Fellowship supports this endangered skill and involves working on commissions and conservation projects.

About the author:

Guest

From time to time we have guest posts from partners, visitors and friends of the Engine Shed.

View all posts by Guest