Creating ‘The Red Forest’: a Gaelic stained glass commission in Glasgow

Materials, Skills | Written by: Gordon Muir | Thursday 3 October 2024

Crafting and conserving stained glass is a vital part of building conservation. Our Stained Glass Craft Fellowship is supporting this endangered skill and has been producing new work inspired by Gaelic heritage.

Gordon Muir is our Stained Glass Craft Fellow based at the Engine Shed, Stirling. Hosted by The Institute of Conservation (ICON) accredited stained glass specialist and native Gaelic speaker Rab MacInnes, Gordon shares how, together, they created six beautiful Gaelic windows for Websters Theatre, Bar and Playhouse (Websters), in Glasgow.

An Endangered Craft

I am really excited to be the Historic Environment Scotland (HES) Stained Glass Craft Fellow. The Fellowship aims to address the traditional skills shortage in this area, which is recognised by The Heritage Crafts Association as endangered in the United Kingdom.

They define historic stained glass window making as the ‘designing and making of painted and leaded stained glass windows on a large scale for architectural settings, typically for use in historic buildings and churches. This is distinct from contemporary or architectural stained glass where windows are generally made from a single sheet of glass and coloured with enamels’.

Left: Rev. Kenneth MacLeod, Gaelic folklorist and writer, is commemorated with this window depicting St Columba at Iona Abbey. Right: The Garrison Chapel window at Fort George depicts St John, the Crucified Christ and St George, erected in memory of the Seaforth Highlanders who died in the First and Second World Wars.

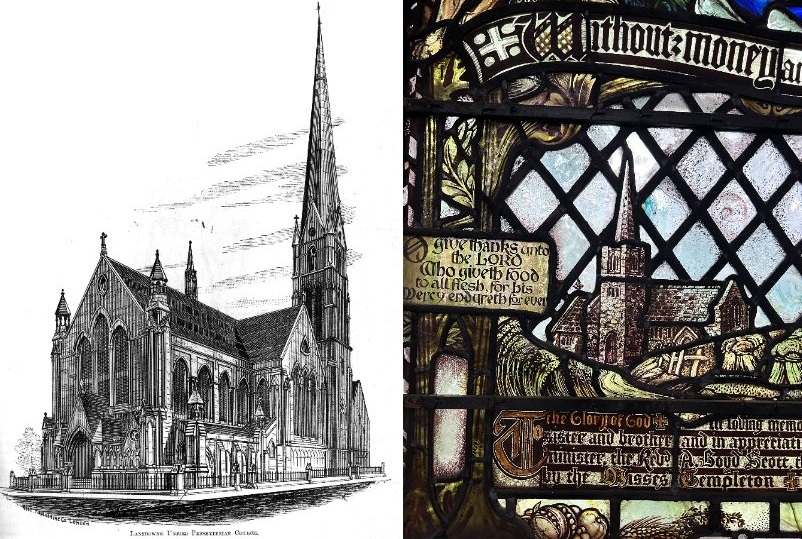

I started my Craft Fellowship in January working at the Glasgow studio of Rab MacInnes. Rab’s work includes stained glass commissions and conservation projects, and one of the first projects we did together was ‘The Red Forest’, commissioned for Websters, the Category A listed former Lansdowne Parish Church on Great Western Road.

Alf Webster’s stained glass windows

Websters is named after the celebrated stained glass artist, Alf Webster, who created several windows for the former church. Alf was one of the most proficient and innovative stained glass artists of the 20th century. Unfortunately, he died in France after being seriously injured during the First World War, but in his short life he managed to create a wealth of work, and was ground-breaking in his approach to stained glass.

Left: Architect’s etching of the former Lansdowne Parish Church, now Webster’s Theatre. © University of Strathclyde. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk. Right: Close up of one if its windows by Alf Webster, 1913. © Gordon Muir.

The windows Alf created survive in Websters to this day, and I hope to be assisting Rab with their conservation in the near future, so they can be seen by the public. In the meantime, Websters has recently opened their renovated Secession Lounge, where you can see The Red Forest windows.

The Red Forest

Replacing textured diamond quarry glass windows (from the French “carre”, meaning square), the new windows were created with generous support from a local donor and friend of Websters Theatre, which is commemorated along one of the window’s edges.

The Red Forest windows were strongly influenced by Alf Webster and Graeme Murray, who studied at the Bauhaus in Germany and explained that Kandinsky set a task for his students: paint a red forest.

The theme draws its inspiration from ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ (The Blue Rider) group of artists. This movement of creatives included Franz Marc, Wassily Kandinsky, Marianne von Werefkin and Elizabeth Epstein. Their work, like that of Alf Webster, was disrupted by the onset of the First World War, and this organic artistic group dispersed, devastated by the loss of life and changing personal relationships.

Wind, Water and Fire windows, part of The Red Forest. © Gordon Muir. Current Gaelic Othographic Conventions would result in ‘Uisge’ instead of ‘Uisce’.

Der Blaue Reiter is derived from Franz Marc’s love of horses and Wassily Kandinsky’s love of horse riding. Colour had spiritual and symbolic associations; they also believed in the connection between art and music, and a spontaneous, intuitive approach to painting. So, as blue horses do not exist, neither does The Red Forest.

Earth, Moon and Sun windows, part of The Red Forest. © Gordon Muir. Current Gaelic Othographic Conventions would result in ‘Talamh’ instead of ‘Thalamh’.

Inspiration from a Gaelic homeland

Rab is a Gael and still has his grandfather’s house where he spent most of his childhood, in Lemreway, South Lochs on the Isle of Lewis. Gaelic was his first language, being used both at home and by his mother when speaking to him.

Whilst studying at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Rab would come home to shear sheep and cut peat. The windows are a manifestation of a mixed youth and language, from looking at the names of Gaelic speaking marshals on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, to going home to fish opposite the Shiant Islands out of Loch Shell.

Aerial view of Lemreway, Isle of Lewis.

Feeling strongly that Gaelic is underused and always keen on promoting his native language, Rab started using Gaelic, Latin and sometimes English in his major windows. As Rab says: “Suas Leis a’ Ghàidhlig” or ‘Up with the Gaelic’.

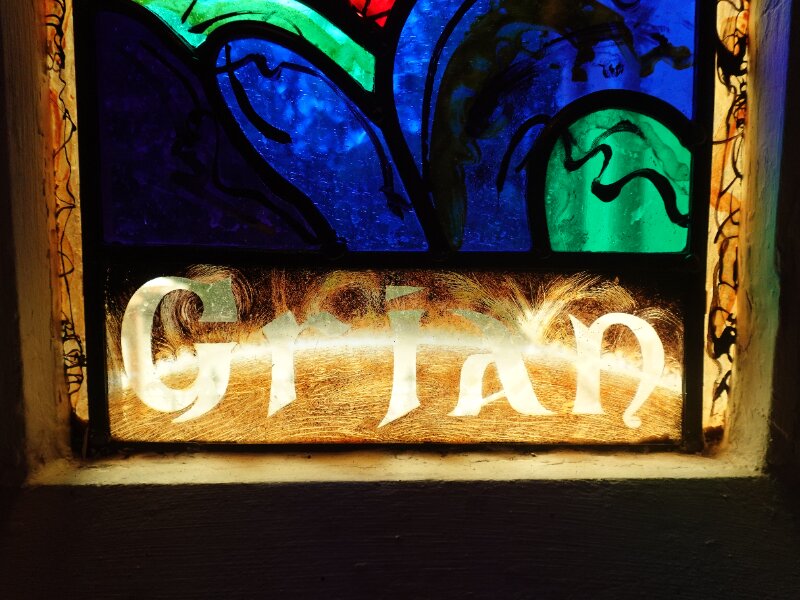

Thalamh (Earth). Current Gaelic Othographic Conventions would result in ‘Talamh’ instead of ‘Thalamh’.

The Gaelic name plates

From the start of The Red Forest project, Rab had decided to give each of the six windows an elemental name plate in Gaelic. He also gave me the opportunity to design them and create some of the illustrations.

My task was to represent the Gaelic words in an impactful way. The Red Forest is rooted in ‘Earth’ (Thalamh), will be in need of ‘Water’ (Uisce), is blown by ‘Wind’ (Gaoth), nourished by the ‘Sun’ (Grian), threatened by ‘Fire’ (Teine), and influenced by the ‘Moon’ (Gealach).

Gealach (Moon).

Elemental illustrations

There are themes of danger and catastrophe embedded in the names; forest fire can be catastrophic, flood can carry chunks of land away and the wind can break trees. Questions about our environment and human influence seemed to be already apparent. Forests host life forms, such as insects, birds, and snakes. All of these seemed obvious choices to include in the design.

Grian (Sun).

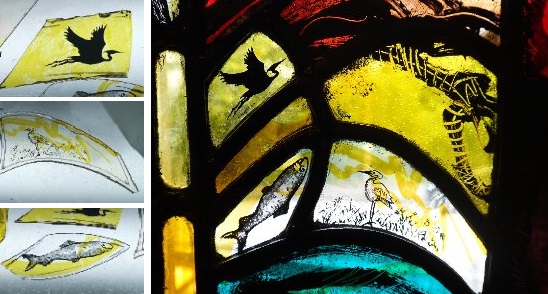

The position of the windows faces the River Kelvin and one of its features is the heron bird, (Corra-ghritheach in Gaelic), which can be seen sitting on one leg awaiting its next meal.

Left: Drawings of the heron and fish on glass, after firing. © Gordon Muir. Right: Drawings placed within the finished window.

My first firings

I wanted my first little firings of illustrations on glass to subtly raise questions. The fish is out of water and upside down. Is it dead, or just leaping out of the water?

There are two images of the heron. In one, it seems quite content, the other heron in flight (in silhouette) looks as though it is leaving, or is it coming back? The other standing heron seems in contrast, settled in its environment.

Uisce (Water). Current Gaelic Othographic Conventions would result in ‘Uisge’ instead of ‘Uisce’.

Learning to use vitreous paint

This was my first time using vitreous paint to draw illustrations on glass. Vitreous paint is a mixture of ground glass and a pigment oxide, or a mixture of metallic oxides such as iron, copper, cobalt, manganese, and others. The ground glass contains silica, alumina, borax, and lead. These are sold in a powdered form, and before its application to glass it must be mixed with oils, or water and gum Arabic as a binder. For permanent adhesion, this must be fired in a kiln.

Mixing with clove oil

Clove oil is an extremely fine, light, aromatic oil used in cosmetics and medicine. For painting on glass, it is an ideal mixing agent for using with a nib pen, when mixed to the right consistency. Clove oil takes a long time to dry, so it is best to fire images soon after completion. When fired in the kiln, the oil burns up and the paint fuses to the glass.

Left: Mixing vitreous paint with clove oil in the studio. Right: The finished window after I drew a snake winding its way through tree branches. The snake looks poised to devour the fly, which has been drawn on a disc of silver stain, representing the Sun. © Gordon Muir.

For the Gaelic name plates, the names had to have a strong pictorial description of the words. Starting with Gaoth (Wind), I used the same mixture of clove oil and vitreous paint to draw the image, which was then fired, and another colouring agent called silver stain.

Gaoth (Wind).

What is silver stain?

Silver stain first appeared in the mid-14th century and is the stain in ‘stained glass’. Its use over the centuries increased because it allowed artists to apply the yellow transparent colour on a clear or light-coloured glass, thus creating an opportunity to have two colours on one piece of glass. This method opened new possibilities for executing decorative parts of the window with more subtlety and finesse.

Teine (Fire).

Today, silver stain is sold in powder form, and composed of silver nitrate and gamboge gum, an orange to brown gum resin extracted from the Southeast Asian trees. It is usually mixed with water, and the gamboge gum acts as a vehicle and binder. It is normally applied to the glass and fired in a kiln. During the firing, this substance will stain the glass yellow. After firing, when the glass is cool, the gamboge is washed away and the clear, transparent yellow appears in its place, permanently embedded in the glass.

Rab’s stained glass studio

I would like to thank Rab MacInnes for welcoming me into his studio to assist with his stained glass work, for passing on his knowledge and I look forward to sharing more of our projects soon.

Left: Rab MacInne s working on The Red Forest in his studio. Right: Gordon Muir, Stained Glass Craft Fellow.

Find out more

Our free building advice section has our latest research and best practice on traditional building materials, components, common defects, and energy efficiency.

Find out more about our Craft Fellowships or get in touch if you’re interested in hosting and collaborating on a Craft Fellowship.

We advertise all Craft Fellowship, Trainee and Apprenticeship vacancies on the Historic Environment Scotland Current Vacancies page, when available.

About the author:

Gordon Muir

Gordon Muir is a Stained Glass Craft Fellow, part of our Trainee and Craft Fellowship Programme, based at the Engine Shed and hosted by ICON accredited stained glass specialist Rab MacInnes. Gordon has a background in Fine Art Painting, Community Arts, and social care with experience in conserving and creating stained glass windows. His Craft Fellowship supports this endangered skill and involves working on commissions and conservation projects.

View all posts by Gordon Muir