The fascinating science of stone-matching

Behind the Scenes, Conservation, Science | Written by: Imogen Shaw | Wednesday 23 August 2023

Science, technology and research have opened up incredible opportunities for learning more about traditional buildings and structures. Join Conservation Trainee Imogen Shaw to discover how Heritage Scientists are using a fascinating technique called stone-matching to care for Scotland’s heritage.

A section of replaced stone as part of the Melville monument.

“How could someone be so stupid – repairing a grey monument with a white stone?!”

These words from a passer-by were recounted to me by Luis Albornoz-Parra, a geologist at British Geological Survey (BGS), involved in the restoration of the Melville Monument in St Andrew’s Square.

The stone repairs at the Melville Monument were, in fact, the best possible replacement. Replacement stone was sourced from Cullalo quarry, the same quarry as the original monument 180 years before. Besides the age difference, this stone was a perfect match!

Conservation works on Edinburgh’s Melville Monument.

This is a rare situation though. There were once around 4,000 building stone quarries in Scotland, but with only 7 continuously producing stone today and 10 intermittently active, it’s almost impossible to get stone from the quarry a monument was originally built with.

The vast majority of modern repairs to historic buildings require a process called stone-matching, where we work out the best possible replacement stone for a building, based on the geological characteristics of the original stone.

Why stone-match?

HES Conservation Scientists inspecting the walls of Castle Campbell.

From the sandstone of city tenements, to Aberdeen’s grey granite, stone is a huge part of our built heritage. Scotland’s diverse geology has created an amazing tapestry of different types of stone buildings across the country. Stone-matching means repairs will see these buildings last well into the future.

In the past, repairs were often made with whatever was available in the local stone yard, matched roughly by colour. However, as science and technology has evolved, we’ve become more aware of stone properties and how they impact a building’s long-term durability and performance. We now know we must carefully consider both the original and replacement stone type when making repairs.

A poor stone match can cause a building to decay quicker. For example, if the replacement stone is more resistant to moisture (has a lower porosity and permeability), water will flow through the less resistant (more porous) original stone worsening its decay. But the opposite can also be true – if the replacement stone is significantly less resistant to moisture than the original, then the repair will decay quickly and may need further work done in the near future.

The best possible stone replacement is the one most similar to the original. This means the entire building can continue to work together and ‘breathe’ naturally.

How is stone matching done?

Stone matching starts with getting a physical sample (hand sample) of the building stone that needs repair.

When we’re doing this at Historic Environment Scotland, we’ll take this back to our lab at the Engine Shed to make observations of the fresh stone and external (weathered) surfaces of the sample.

Then we have something called a thin section made for further analysis. This is a small stone sample attached to a glass slide. The stone is ground down until it’s thinner than a human hair. This lets light pass through it, so we can analyse it under the microscope. The process of describing a stone in thin section is called petrography.

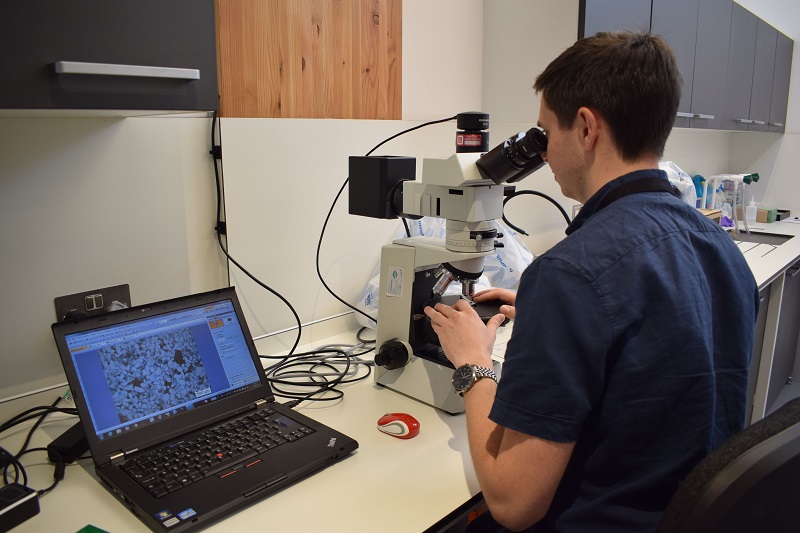

HES Conservation Scientist Callum Graham looking at a stone sample under the microscope in our Engine Shed lab.

Using this thin section, we can record the percentage of all the different minerals within the stone, and the size, spacing and connectivity of the stone’s pores. We can also learn more about other distinctive features of the stone, such as any mineral alignment or the presence of fossils!

We’ll then analyse thin sections and hand specimens of potential replacement stones in the same way. This means we can compare the results of the original stone, and the potential replacements, to select the best match.

Our aim is to match the stone properties as closely as possible. If a similar stone can’t be found, then the replacement can be slightly less durable than the original stone. This means it becomes ‘sacrificial’: it will take slightly more water damage, and be more effective at protecting the original building.

What about how a stone looks?

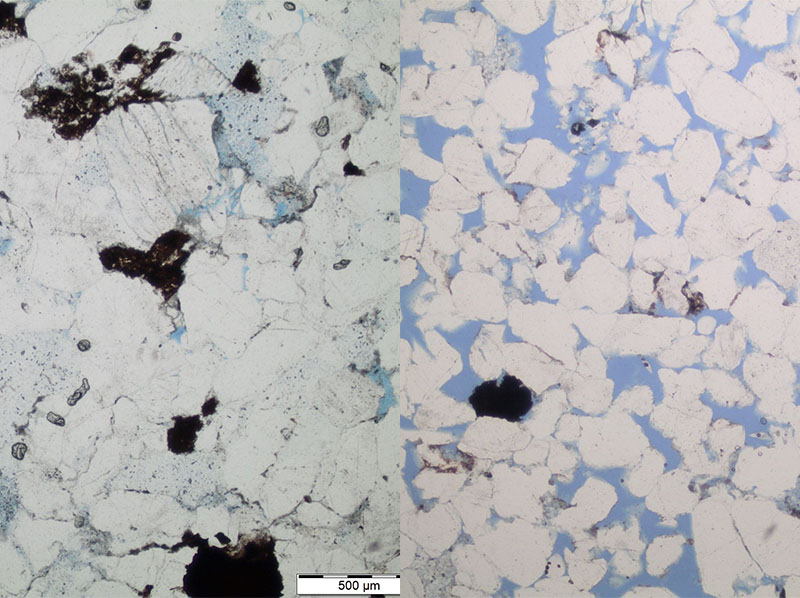

These two stone samples are very similar in appearance, but that alone doesn’t make them a good stone match. Left: Bearl sandstone, Right: Darney sandstone

If the geological properties of a replacement stone are well matched to the original, the stone should look similar over time.

Original stones are often several hundreds of years old, and so have experienced a significant degree of weathering and surface staining compared to their fresh replacements. Stones which initially look similar can also weather to significantly different colours over time. If the stone match is a good one, the stone should weather in well.

Matching on colour alone is asking for trouble though, as a replacement stone that is a good colour match can still be significantly structurally or compositionally different!

While Bearl and Darney sandstone look similar to the naked eye, they look quite different under the microscope, which can help determine if they’re a good stone match. Left: Bearl sandstone, Right: Darney sandstone.

The future of Scotland’s stone buildings

With only 17 building stone quarries actively producing in Scotland today, our unique built heritage is at risk. Sourcing appropriate good-quality replacement stone, in keeping with the local character, is becoming increasingly challenging.

Ultimately, Scotland needs its most culturally significant building stone quarries to be re-established, so like-for-like repairs can be made. This would also supply high-quality, local building stone for the newbuild market at a fraction of the environmental cost of imported stone products. Projects for other building materials, like this slate project on the Island of Luing, are already looking at ways Scotland can re-open small enterprises for a more sustainable future.

Find out more

If you’d like to know more about stone, explore our publications about stone buildings which include advice on stone cleaning, stone floors and a series of case studies.

We also have information on the characteristics and history of sandstone and how to deal with sandstone erosion.

If you’re making a traditional building more energy efficient, read our guide on how to insulate stone walls.

About the author:

Imogen Shaw

Imogen Shaw was a Conservation Trainee, working in the Traditional Materials and Heritage Science teams at the Engine Shed. She graduated in Geology in 2022 and enjoys applying scientific techniques to the conservation of historic buildings.

View all posts by Imogen Shaw