How the Romans helped build Scotland

History, Materials | Written by: Jennifer Farquharson | Friday 22 May 2020

The Antonine Wall was the Roman’s northern most frontier. Some might think that they didn’t have much of an impact in Scotland, but we can trace much of our historic environment back to their innovation. Read on to learn how the Roman’s helped build Scotland.

Building brick empires

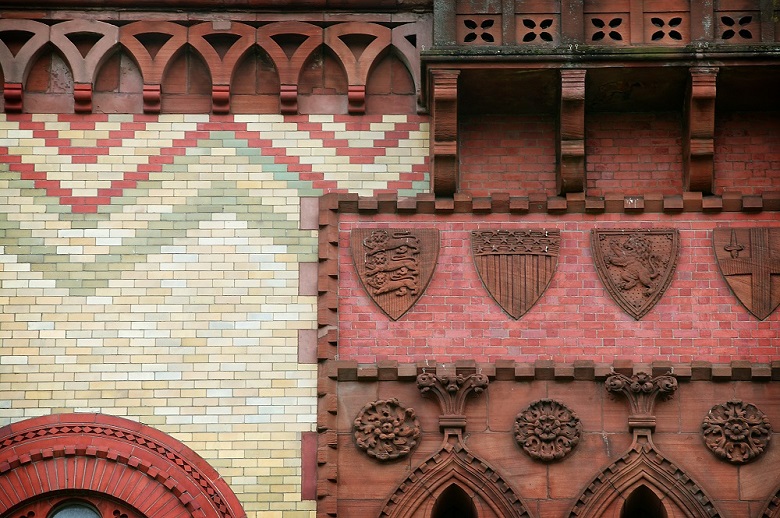

Brick may seem a bit ‘every day’ to us now, but it was brought to Scotland by the Romans in the first century AD. It was a foundation of their empire and they used it to build cities, roads, fortifications, and more.

Brick mostly disappeared with the Romans, but centuries later we used it to build legacies of our own. Everything from 17th century country estates to 19th century industrial landscapes are built in brick.

Learn more about brick.

Magnificent marble

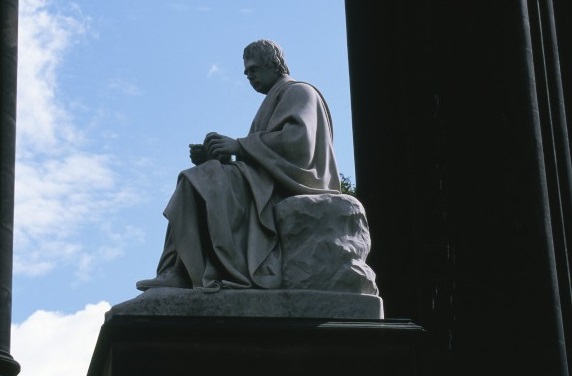

The Greeks and the Romans might not have always seen eye to eye, but that didn’t stop the Roman’s from loving Greek white marble. Though around the first century AD they started to mine marble quarries in Northern Italy, including Carrara marble in modern Tuscany.

It has been used to create sculptures like Michelangelo’s David, to help build places like the Pantheon, and even in Edinburgh’s own Scott Monument. The statue of Sir Walter Scott and his dog Maida are carved from one 30 ton block of Carrara marble. It took 6 years to complete.

Make it with mortar

Although we don’t know the exact origins of lime, we think it was most likely brought to us by the Romans. The process of making lime hasn’t changed much over thousands of years.

Limestone is burned in a kiln at around 850⁰C, which creates quicklime. The quicklime is slaked in water which creates a huge exothermic reaction. This slaked lime is mixed with an aggregate and water to make lime mortar.

Traditional buildings in Scotland were often made using a lime mortar, which is more breathable than cement-based mortars.

Learn more about lime.

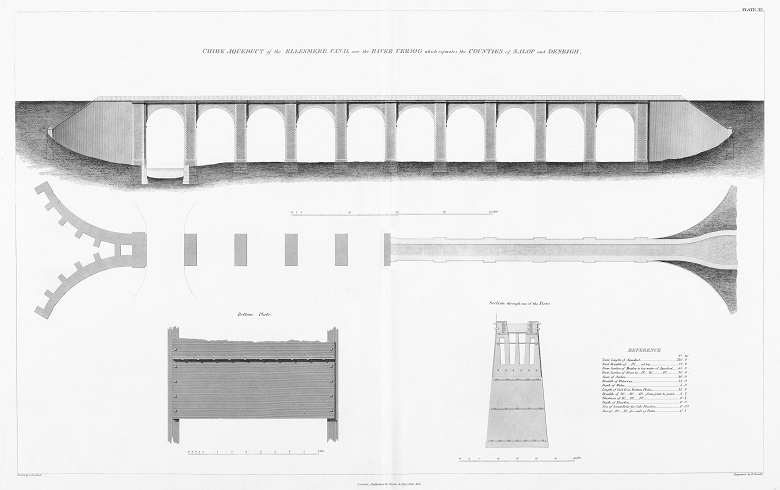

Structures in cement

Concrete pre-dated the Romans, but they took it to new heights. By mixing volcanic ash (pozzolana) with burnt limestone slaked with water (hydrated lime), the Romans created hydraulic cement concrete.

This allowed them to build higher, stronger, and more durable structures, some of which still last today. In Britain, cement and concrete were part of the 18th century advances in civil engineering including the Glenfinnan railway viaduct, The Bell Rock Lighthouse in Angus and the Forth Bridge concrete and masonry piers.

Masonry magic

Like brick, ashlar masonry was introduced to Scotland by the Romans, and didn’t survive their retreat from Britain. It wasn’t until monastic structures like abbeys were being built in the 11th century, that this technique of building with large, rectangular squared-edged stone blocks was revived.

It became the favoured means of constructing country mansions like Duff House in the 17th and 18th centuries. Technology made it more affordable during the 19th century so it became more common.

Learn more about stone.

Learn more about Scotland’s traditional building materials and how to care for them.

About the author:

Jennifer Farquharson

Jennifer Farquharson is a Content Officer at the Engine Shed. Jen creates engaging content about our sustainable conservation centre.

View all posts by Jennifer Farquharson