Alexander Greek Thomson: Glasgow’s Great Visionary Builder

Architecture, Heritage, History | Written by: Abi Guthrie | Thursday 9 April 2020

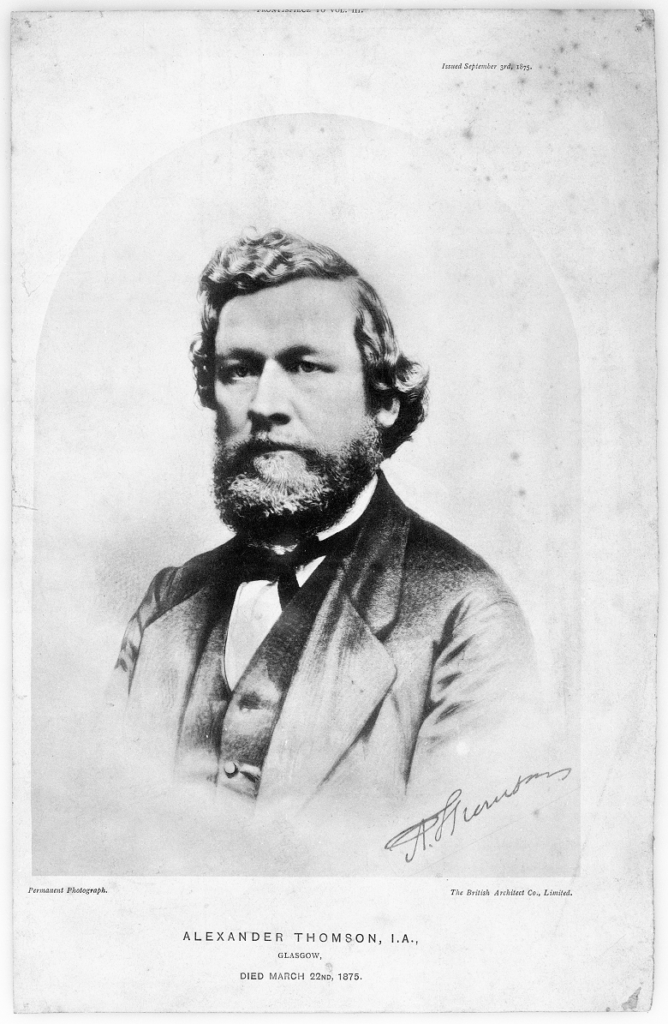

Known for his innovative use of new building materials and his love of Classical architecture, Alexander “Greek” Thomson is one of Scotland’s most influential architects. As his work becomes increasingly popular over 140 years after his death, we take a look into his life and achievements.

Who was Alexander “Greek” Thomson?

Alexander Thomson was the seventeenth son of bookkeeper John Thomson. He was born in Balfron, Stirling on 9th April, 1817.

His father died when Thomson was seven, followed by his mother and four older siblings. Thomson and his family were raised in the poor outskirts of Glasgow by the eldest brother William, a classical scholar.

In 1847 Thomson married Jane Nicholson, daughter of the noted Glasgow architect Peter Nicholson. The couple had eight children, four of whom died during the 1854–56 cholera epidemic in Glasgow.

Thomson’s family losses and personal health seem to have influenced his architectural designs. He wanted his tenements to improve the living conditions of the working classes. He proposed startlingly modern means to do so.

After battling asthma and bronchitis for most of his life, Thomson died on the 22nd March 1875 in the house he designed himself at 1 Moray Place in Strathbungo. He was buried in Glasgow’s Southern Necropolis.

A young talent

At age 12, Thomson started work as a clerk at a lawyer’s office in Glasgow. He would sketch in his spare time. When he was 17, his skill was recognised by architect Robert Foote.

Foote was so impressed that he invited Thomson to begin his articles (an arrangement similar to an apprenticeship) at his own architectural practice.

After that, in 1848, Thomson began a very successful practice with brother-in-law John Baird. Then later, with his brother George, he established the firm A & G Thomson.

Thomson was a very successful architect throughout his career. He amassed a large portfolio of villas, terrace cottages, ecclesiastical structures, warehouses and tenement buildings.

Classical influences

Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson is remembered as being prolific for his contribution to Scottish neo-classicalism from the Grecian, Egyptian and oriental influences in his designs. This led to the moniker of ‘Greek’ Thomson. His large portfolio included villas, terrace cottages, ecclesiastical structures, warehouses and tenement buildings.

However, Thomson never actually left Scotland. Instead, he got his inspiration from Foote, who travelled to the ruins and museums of Greece and Italy and had a collection of classical art plaster casts.

Champions of ironwork architecture

In 1836, Foote withdrew from his architectural practice for health reasons. After that, Thomson completed his articles with John Baird I, a Victorian champion of iron architecture.

During the 1850s, Glasgow architects began to use cast and wrought iron in their designs. However, Thomson had been working with these materials since his time with Baird during the 1830s and 1840s, who took advantage of the structural benefits of iron.

Thomson’s ironwork included decorative balustrades, balcony fronts and outdoor lamps that you can still see today on Millbrae Crescent, Westbourne Terrace and Moray Place in Glasgow.

A unique example of Thomson’s use of ironwork in Glasgow is in the Buck’s Head Building on Argyll Street. This was the first time that Thomson had used elevated iron columns within his neo-classical designs. Today, it is still a major city landmark.

The grandest terrace in Glasgow

In 1867, Thomson was drafted to design the grandest terrace in Glasgow, named Great Western Terrace. Despite a lack of Thomson’s signature motifs, the buildings still features the architect’s classical columns and intricate ironwork.

One of the builds became the home of William Burrell, a Victorian Scottish shipping merchant and philanthropist who would end up accumulating what we now know as the Burrell Collection.

Where are they now?

Thomson used the best and biggest stones for the construction of his buildings. He believed that there was “nothing more humiliating or repugnant than decay”. But due to the wet climate of western Scotland, improper maintenance and neglect, a number of Thomson’s buildings have fallen into disrepair. Despite this, many have survived the test of time.

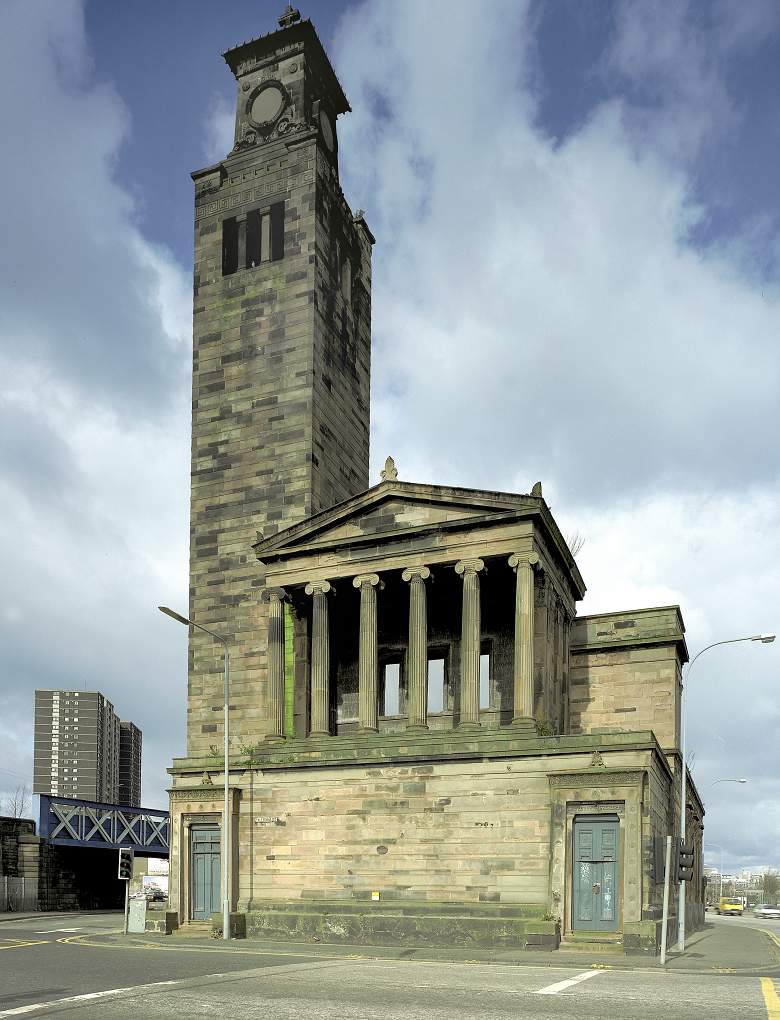

Out of three churches designed for Glasgow by Thomson, St Vincent Street is the only survivor. Completed by Thomson and his brother George in 1859, the church was built on top of a large plinth and was designed to resemble a Greek revival style temple. The façade features six grand columns that support a full classical pediment. Inside, the gallery is supported by colourful Greek cast-iron columns.

Upon the death of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson in 1875, a travelling scholarship was founded in his name and awarded every three years for the study of ancient classical architecture.

In 1890, Charles Rennie Mackintosh was awarded this scholarship and embarked on a sketching tour of Europe. Over 140 years later, the scholarship is still active today.

About the author:

Abi Guthrie

Abi Guthrie was a Technical Outreach and Education Trainee, working in the content team at the Engine Shed. Abi graduated in History at the University of Stirling in 2018.

View all posts by Abi Guthrie