A slate tour of Scotland: shaping historic roofs

Materials | Written by: Guest | Friday 22 November 2019

Slate was once one of the most important building materials in Scotland, with a thriving industry boasting over 80 quarries. Today, it still covers the roofs of many older buildings we know and love.

In this blog join us for a tour around the country, from the Highlands to Scotland’s very own “slate islands”, to learn all about this incredible material and how it began to form 700 million years ago.

Ballachulish: The strong slate

A slate quarry at Ballachulish

Nestled among dramatic hills and beautiful scenery, the village of Ballachulish was once the “slate capital” of Scotland. You can still see the disused quarries nearby as well as this slate in buildings across Scotland.

Ballachulish slate was formed under higher temperatures and pressures and contains more quartz grains than other regional slates, making it the strongest. This is the reason it dominated the Scottish slate industry for a hundred years.

To look at, it’s grey and black with a sheen to its surface. It’s not uncommon to find golden cubic crystals of pyrite (commonly known as ‘fool’s gold’) within the slate.

When you think of slate, roofs might only come to mind. But did you know that this type of slate was once used to make gravestones? If the men working in the slate quarries found a particularly large and thick slab of slate, they would take it home with them and keep it propped outside of their house to be eventually used for their own grave.

Slate gravestones are rare in comparison to sandstone, granite and marble. So if you spot one, know you’re seeing something quite special!

Easdale: The ripple effect

Easdale Quarry

In the Firth of Lorn, the “slate islands” were once at the centre of the British slate industry and are thought to be the place where the slate industry in Scotland began! Can you imagine that these idyllic islands once had a community of thousands working across several quarries? The slate from Easdale, one of the smallest of these islands, helped build major cities around the world.

The slate from Easdale is similar to Ballachulish because they both contain pyrite, or “fools gold”. This slate can be distinguished by its ripples or crinkles on the surface. These were formed by two pressures from different directions pushing minerals together, creating folds.

Easdale slate can be found on many of Scotland’s castles and cathedrals, including Cawdor Castle in Inverness-shire, Ardmaddy Castle in Lorn, and Glasgow Cathedral.

You’ll also see it on the canongate wall of The Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh. While you’re there, have a read of the inscription of Sir Walter Scott’s “Heart of Midlothian”.

Macduff: The rough one

Hill Of Tillymorgan, Quarries

As well as slate islands, Scotland also had the “slate hills” of Kirkney, Corskie, Foundland, Tillymorgan and others in the North East of Scotland. This is where Macduff slate comes from, taking its name from the little seaside town of Macduff in Aberdeenshire.

In comparison to Ballachulish and Easdale slate, Macduff slate is a bit rougher. It is coarse grained and has a rough and gritty texture. You can even sometimes see small grains of quartz on the surface.

Generally blue or grey in colour, Macduff slate sometimes has a purple hue because of the presence of the iron ore haematite. The dark spots dotted throughout it are a unique characteristic of this slate. They come from a mineral called chlorite.

Due to the lack of suitable transport links back in the 18th century, Macduff slate remained in the North East, but can still be seen on local buildings today. This slate has also been used in an artwork by Richard Long called the Macduff Circle, which can be found in the grounds of the Dean Gallery.

Highland Boundary: A touch of tartan

Aberfoyle Slate Quarry

Highland Boundary slate can be found along The Highland Boundary Fault, which extends across Scotland from the Mull of Kintyre in the west to Stonehaven in the east, separating the middle of Scotland and the Highlands. It was quarried in many places such as Arran, Bute, Dunkeld and Aberfoyle.

Like Macduff slate, Highland Boundary slate was constrained to roofing local buildings due to the lack of suitable transport links. This means many of the buildings in Stirling and the rest of the Central Belt were built using Highland Boundary slate.

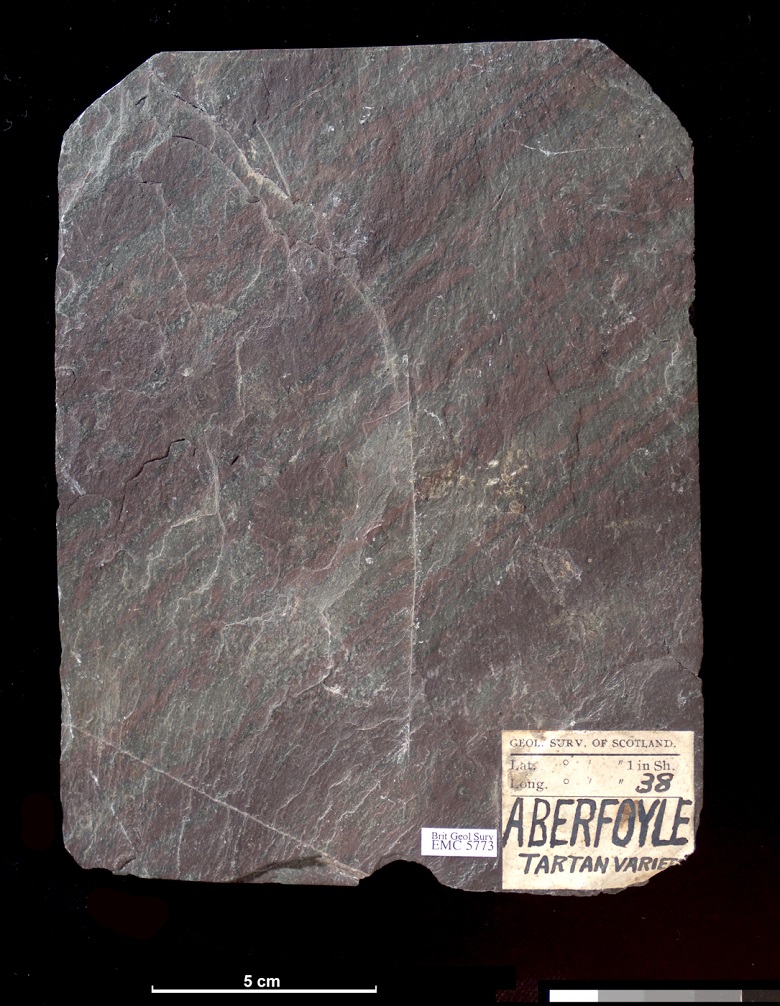

This slate was formed from fine grained mud. Similar to Macduff slate, it can vary in colour, from blues and greys to greens and purples. Interestingly, bands of different colours can also be seen on the same piece of slate. This is caused by alternating sedimentary beds that have slightly different compositions. Some beds have a higher concentration of the iron oxide haematite which gives it a red/purple colour. We call these slates “tartan slates”.

This tartan slate comes from Aberfoyle. At one time, it was used as a marketing feature for Scottish slate.

“Tartan” slate from Aberfoyle Slate Quarries

So how is this slate made?

In its earliest form, slate was created from fine grained sediments like mud and silt. These piled up and formed layers called beds. The layers then compacted into mudstone or shale.

To turn these sediments into slate, the material went through a process called regional metamorphism. Metamorphism is when rocks are buried and subject to intense heat and pressure within the earth, which alters their characteristics. Can you believe that this happened around 450 million years ago when the Iapetus Ocean closed and continents collided to form Scotland?

Sea floor sediments were squeezed, flattened and stretched between the colliding continents and subject to high temperatures. The minerals inside the rocks were moulded by the crushing forces around them, and eventually overlapped like fish scales. This is why Scottish slate is strong and durable, and what gives it its “slaty cleavage” – in other words, its ability to split easily!

There’s nothing quite like it

Slate plays a very important role in the look and feel of traditional Scottish buildings. It’s Scotland’s rich and diverse geology that gives our roofing slate its variety in texture, colour and thickness. This gives Scottish roofs a distinctive appearance that can’t be replicated using slate imported from other countries. Even the way the roof is laid out is different in Scottish roofs, with larger slates being used at the bottom and smaller slates being used at the top (this is a practice called diminishing courses).

An example of diminishing courses with the larger slates at the bottom and the smaller ones up top.

With no slate quarries operating in Scotland today, and the reserves of good quality recycled slate slowly running out, we are left with no choice but to use non-Scottish slates. This means many of our buildings needing roof repairs show obvious patches that sit in stark contrast to the rest of the roof, or sometimes entire roofs are replaced with imported slates and look extremely different to the surrounding buildings.

As this issue becomes increasingly critical, a new source of Scottish slate will need to be identified.

A traditional Scottish roof covered in Easdale slate next to a roof using imported slate to its left. Can you spot the dark patch of imported slates used in a repair on the top of this roof?

Do you think you can tell the difference between a roof using imported slate and a traditional Scottish slate roof? Next time you see a roof stop and have a look at it – maybe you might even be able to tell what area of Scotland the slate came from!

Learn more about Scottish slate, including its history and how to care for it with our slate building advice.

About the authors

Natalie is a Traditional Building Materials trainee with a focus on stone and slate. She has a degree in Geology from the University of Glasgow and loves exploring Scotland’s natural landscapes.

Abi Guthrie is a Technical Outreach and Education Trainee, working in the content team at the Engine Shed. She is from Dunblane and graduated in History at the University of Stirling in 2018. Abi is getting experience in creating engaging content about conservation.

About the author:

Guest

From time to time we have guest posts from partners, visitors and friends of the Engine Shed.

View all posts by Guest