The traditional skills that built Scotland

Heritage, History, Materials | Written by: Guest | Tuesday 27 August 2019

Scotland’s older buildings give character to our streets and towns. In every brick, slate and piece of stone there’s a story to be told about how our ancestors worked and lived. Now, these very same materials and skills have an important role to play…

Historically, people had to use whatever came to hand to build their homes. Skills were passed down from generation to generation and some stretched back hundreds of years.

Today, expert craftspeople are using these same skills to conserve Scotland’s valuable buildings for future generations, but over time, the popularity of some of these techniques and materials has changed. Here we take a look at some of the traditional skills and natural materials that built Scotland.

Earth building – an ancient art

A thatched byre with a turf wall

People have used earth to build walls for thousands of years. Not only is it plentiful, it’s also inexpensive. Like most natural building materials, earth resources differ from place to place. Earth buildings come in many different forms and can be made with turf, mud wall, clay and bool and shuttered clay. These earthy materials can be used by themselves, or combined with lime, timber, straw and stone to suit a mix of climates.

Buildings made with earth can be difficult to spot. Sometimes they were covered with brick, stone or rendered with lime or cement for added protection. And, being made with natural materials, it’s much easier for them to blend back into the landscape as they degrade!

Earth buildings still survive in Perthshire, Angus and the South-West of Scotland, but earth fell out of favour when other building materials became popular…

The final straw for thatch

A standalone thatched building in Scotland

Just like earth, thatch eventually fell out of fashion. But this material also goes back a long, long time. In fact, even Scotland’s first settlers used plant material to cover their roofs.

Thatch usually consisted of heather, straw, reed, bracken, broom or marram grass. The plant types used would be dependent on local availability and land management. But what caused people to stop using this natural material?

During the 19th century, many people moved from rural steadings to towns. New methods of transport, specifically railways, improved access to cheaper and more durable materials like corrugated iron, slates, wooden shingles and pantiles. Although remote communities continued to use thatch as a roofing material, and still do today, depopulation of the countryside and improvements in living conditions meant that this tradition declined.

Now, the skills of thatcher’s are crucial in the preservation of the around 200 thatched roofs that still survive in Scotland. Thatched roofs need to be regularly maintained, and a lack of materials and investment has led to the sad collapse of many of these roofs.

Working with wood

Edinburgh Castle’s hammerbeam roof

Joinery is another craft skill that’s age old. Edinburgh Castle’s surviving 16th century hammer-beam roof is one of the most important timber roofs in Scotland. It’s ornately decorated with carved human and animal heads. This spectacular roof would have begun its life in a medieval joiner’s workshop! But we know the wood for this roof began life elsewhere in Norway.

The word joiner comes from the work that they do, which is ‘joining’ wood together. These craftsmen traditionally make ornate woodwork, like doors, window frames and furniture.

Axes, saws, chisels and gouges are tools that joiners use to cut and shape wood. Hand planes help to smooth and flatten the surface of the wood. Joiners are so skilled in making sure each piece fits together perfectly that they do not use any metal or glue to keep their work together.

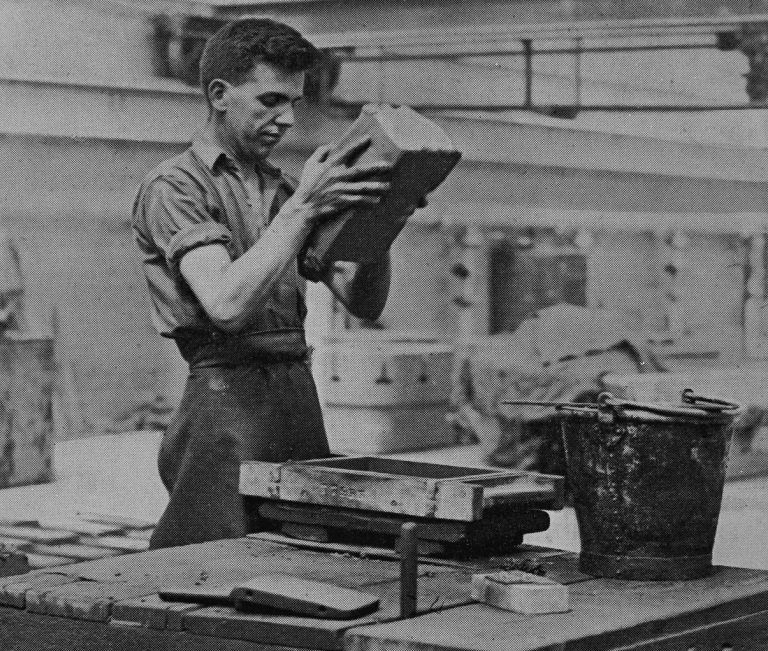

Shaping the future brick by brick

The Gourock Rope Works Factory building in Port Glasgow

We see brick every day – you can find it anywhere in Scotland. It’s been part of the country’s built heritage for at least five thousand years, and has stood the test of time.

Bricks are created with clay and shale. First, the clay is excavated and washed to remove any vegetable matter or stones before its moulded. Traditionally, brickmakers used their hands to form the clay into rectangles, but sometimes they would use a steel-lined timber mould. Up until the 1840s every brick made in Scotland was moulded by hand.

© North Lanarkshire Council. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

During the industrial revolution, brickworks were focused in the central belt. It was during this time that brick began to boom, being used extensively for the factories and industrial buildings that changed the shape of our towns.

Today, machinery usually cuts or presses the clay into bricks. After the shaped blocks are dried on a shelf, they are ‘burned’ or fired in a kiln, the finished bricks are built together using mortar.

A bricklayer’s tools include picks, crowbars, shovels, and a range of specialty tools. Brick trowels are used to spread mortar on bricks, and rammers (a long rod with a flat metal plate at the base) are used to “tamp” down a surface to make it flat and sturdy. The skills of brickmakers and brickworks are very important because they help build strong and long-lasting structures like Gourock Rope Works in Port Glasgow.

A nation of stone

Stonemasonry is one of the world’s most ancient craft skills. For thousands of years, stone has been laid upon stone to create some of Scotland’s most iconic historic buildings. As time went on, stonemasons creatively came up with new ways to use stone, designing columns, arches, buttresses and intricately carved designs.

Dryburgh Abbey on a sunny day.

Unlike earth and thatch, whose use has waned, stone has stood the test of time. But it’s no surprise that Scottish stone is still being used today. Scotland produces some of the world’s finest natural building stones. However, today there are far fewer quarries than there once was. 150 years ago at Scotland’s peak of stone construction, Scotland boasted over 750 stone quarries. Now, there are only around 10.

When caring for older buildings, using the right type of stone is vital to long-lasting repairs. Scottish stone can also be seen in more modern buildings like the Museum of Scotland and Scottish Parliament, as well as many council houses as a result of the 1919 Housing Act.

The Scottish Parliament Building in Edinburgh

About the authors:

Abi Guthrie is a Technical Outreach and Education Trainee, working in the content team at the Engine Shed. She is from Dunblane and graduated in History at the University of Stirling in 2018. Abi is getting experience in creating engaging content about conservation.

Maddisen Fostyni is a student from Arcadia University, USA. She was on placement with the Engine Shed to develop skills in outreach, education, and content development.

Get more information on Scotland’s building materials and learn how to care for them.

About the author:

Guest

From time to time we have guest posts from partners, visitors and friends of the Engine Shed.

View all posts by Guest