An Industrial Cathedral: Refreshing the Roof of the Engine Shed

Conservation, Industrial Heritage, Materials | Written by: Sophie McDonald | Friday 16 June 2017

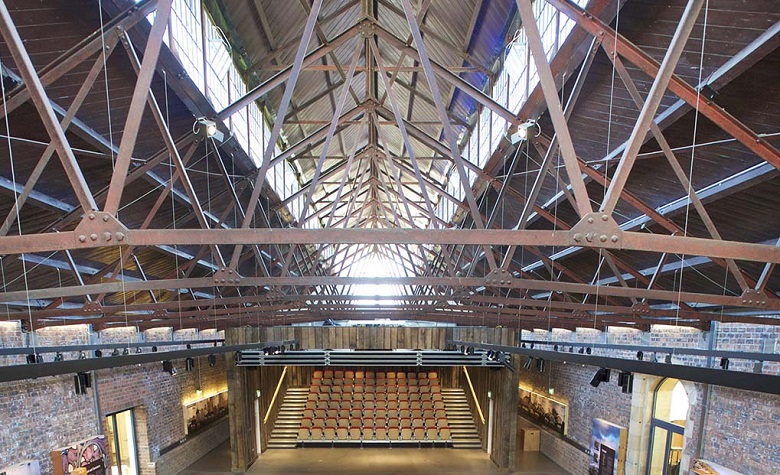

The metal frame of our roof is one of its most impressive features, making the space feel like an industrial cathedral. As well as being beautiful, it’s also important to the building’s integrity, so making sure that the roof was water and weatherproof was a key part of conserving our building.

More than a hundred years after it was first built, the metal roof structure is still in remarkably good condition.

Our roof before conservation work began

Identifying the ironwork

We carried out X-ray fluorescence testing on the metalwork, to confirm what type of metal was lying under the layers of grime and old paint. Five samples were taken from different points of the structure. In some places, we had to remove the rust and old coatings that had built up over the roof’s lifetime, so that the bare metal could be tested. This was to make sure that it was definitely the metal roof structure itself being tested, not any paint or rust on its surface.

Testing the roof trusses

X-ray fluorescence involves firing an x-ray beam from a hand-held analyser at a surface. This displaces electrons from atoms in the metalwork, destabilising the electrons within the atoms of the substance being tested. This causes them to give off energy. The energy emitted from the substance is then measured by the analyser, and can tell us what chemical elements that substance is made up of. In the case of the Engine Shed roof, the metal’s chemical composition was consistent with an early form of steel, rather than wrought or cast iron.

A traditional technique

Armed with the knowledge that the roof structure was made of steel, it was time to decide what (if any) treatment was needed. The steel was in very good condition. There wasn’t much corrosion, and it was confined to the surface of the metalwork. Rust like this can actually protect the metal, forming a layer of defence against the elements. The steel is indoors, in a dry environment which helps to protect it from further corrosion. In cases like this, it’s often best to leave this stable layer of rust untouched. This is because some cleaning techniques can actually harm metal surfaces.

The trusses before conservation work – you can really see the rust

The metalwork was cleaned gently by hand, using bronze wire brushes. No water was used – if it became trapped around joints or rivets it could cause the metal to rust more severely. A light layer of linseed oil was applied to the steelwork. Linseed oil dries to a solid finish, protecting the steel and “reactivating” older layers of linseed oil-based paint. Linseed oil is also used in oil-based paints and glazing putty, or as a finish for wood.

Although some linseed oil is edible – it’s eaten with quark (soft cheese) and potatoes in some European countries – the type we used at the Engine Shed definitely isn’t edible! It’s known as “boiled” linseed oil, although it hasn’t actually been boiled. Instead, various ingredients have been added to help the oil to dry faster.

The Engine Shed’s roof now

Although our conservation of the Engine Shed’s roof has been quite minimal, you can see a real difference when comparing images from before and after our work. The combination of high-tech and traditional technologies we’ve used should ensure that this incredible industrial structure stays in good condition for many years to come.

Find more information on caring for ironwork in traditional buildings here.

About the author:

Sophie McDonald

Sophie worked as a Digital Content Officer with Historic Environment Scotland until 2017, spending her time looking after the Engine Shed's blog posts and social media channels.

View all posts by Sophie McDonald