Searching for the stones that built Scotland

Materials, Science, Skills | Written by: Sarah Hamilton | Wednesday 30 October 2024

Scotland’s geology is hugely diverse. Think of the distinctively different appearances of the ‘Granite City’ of Aberdeen, the local red sandstones used in the Dumfries area, and Edinburgh, known as the ‘Grey Athens of the North’.

The Historic Environment Scotland Heritage Science team, based at the Engine Shed, are surveying stone types at the 300+ properties in our care. Join Conservation Scientist, Sarah Hamilton, to find out more.

Left to right: granite of St Machars Cathedral, Aberdeen; red sandstone of Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfries and Galloway, buff sandstone in Charlotte Square, Edinburgh.

How can surveying stone help us?

The historic stone properties we care for have been around for centuries. The more we know about how they were built, the better we can care for them.

We’re collecting information on stone at our sites to better understand the materials used for construction in each property and within each region.

This work is already helping to inform conservation repairs at some of our sites. In the face of our changing climate, it will allow us to better understand the behaviour of different building stones. With only a handful of building stone quarries still operating in Scotland today, it also helps us to understand where we need to source better matching replacement stones for conservation work, perhaps by reopening old quarries.

The team at the Scottish National War Memorial, Edinburgh.

Building a picture of Scotland’s stone

The survey is a partnership with the British Geological Survey (BGS). Together, we’ve developed a digital system for recording the characteristics of each stone type we see on our sites. That can often involve a surprisingly large number of stone types. It includes not only the original building stones, but 18th/19th century restoration work, more recent repairs and all manner of stone types used for paving and roofing!

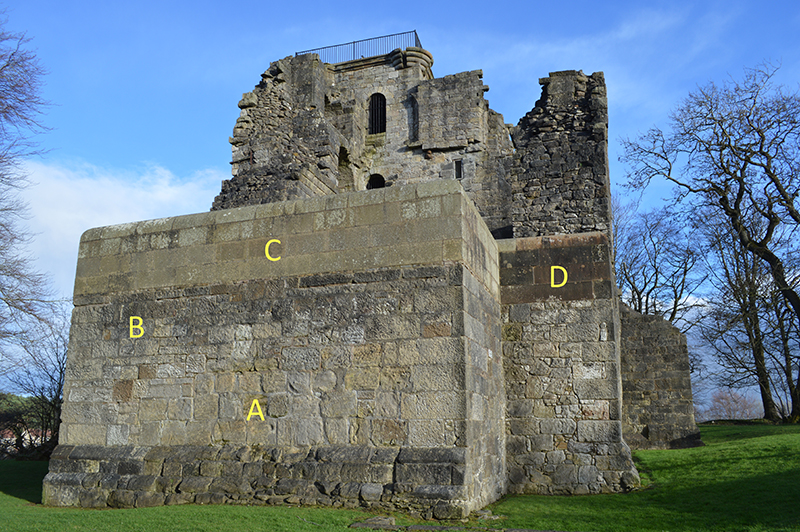

The different types of stone used at Crookston Castle

At Crookston Castle, we identified eight stone types. Just on this stone wall section, you can see:

- the main grey sandstone (a)

- also as smaller, more regularly shaped blocks from a late 19th/early 20th century restoration work (b)

- a buff sandstone for the late 20th century parapet walls (c)

- a red sandstone used for the recessed sections of the same parapet walls (d)

We take this data and combine it with analysis of samples where possible. We can’t remove samples from our properties, but we are able to work with:

- small fallen fragments, after confirmation they won’t be reattached or be of any interpretive value

- stone which has been removed for necessary repairs

The aim is to be able to determine which building stone formation the stone belongs to, and where possible, which quarry or group of quarries it came from. We would not do this for every stone type we identify, only the most ‘significant’ ones – in other words, those that are of historic use and/or used most extensively in the property.

To build an initial picture of the current condition of the stone types, we also undertake a brief ‘decay assessment’. This involves looking at one or two representative sections of the building and recording the different types of decay affecting each stone type. This might include the different mechanisms that are causing surface decay, any salt growth, cracks, surface soiling or biological growth such as moss, lichens or other plants.

Two decay patterns from around Scotland. Left: alveolar weathering, Broughty Castle – © Marli de Jongh. Right: coving resulting from the presence of hard, cementitious mortar (Kelso Abbey)

Armed with all of this information, we can start to gain a better picture of the distribution of different building stone types used across the country, an indication of their performance and where future work should be focused.

Growing the database

When we have identified a building stone formation used in one of our properties (known as ‘provenancing’), we add this information to the Building Stone Database for Scotland (BSDS). This is an ongoing joint project between HES and BGS and provides an online and fully searchable resource recording all the known building stones of Scotland, along with details of associated quarries. It also includes built sites where building stone types are known to have been used and the records of stone samples held in the BGS reference collection. The database is growing all the time. We’ve already added new building stone quarries to the database, both through archive research while trialling our sample analysis and provenancing systems, as well as during site surveys.

Quarry hunting!

‘Quarry hunting’ is an entertaining activity to do at the end of a survey day, if historic maps or records suggest potential nearby stone sources worth investigating.

Disappointingly, sometimes these just can’t be found, are inaccessible or have been completely infilled. However, it’s very satisfying to find a nearby exposed old quarry where the stone displays all the same features as seen in the building, especially when this validates a written source and can be attributed to the building with a fair degree of confidence.

Monkredding Quarry, near Kilwinning.

Local stone?

We mention ‘nearby quarries’ as historically stone was typically considered to have been sourced from no more than a mile away. This is due to the difficulty of transporting such a heavy material before the advent of canal transport and the railways. We may be beginning to challenge this notion for some higher profile properties we’ve surveyed, particularly some medieval abbeys.

In some cases, our work indicates that superior quality stone, better suited to carving decorative features than the underlying building stone, was sourced from much further afield. This can be seen on a number of sites in Dumfries and Galloway, where much of the underlying geology is Southern Uplands Greywacke, a dark grey sandstone useful for rubble walling but not for carved features. Instead, the sites use a pink to grey coarse gritty sandstone for window and door surrounds and quoins forming the corners of buildings. This stone formation isn’t currently recorded as a building stone in the BSDS (but will be as soon as we further analyse our data), and it’s also found a reasonable distance from several of the properties where it has been used. Perhaps there is a land or property ownership connection here? Answering these questions will form part of our research during the future stages of our work and we hope these findings can also contribute to our understanding of historic building practices.

The two different stone types often found in Dumfries and Galloway.

How to get involved

What are the stone types in your area? If you work with traditional buildings, do you know what stone they are built from? Have a look at the BSDS to find out more! You can also contribute evidence of stone types on buildings that aren’t currently recorded in the BSDS. You can also use Canmore, the National Record of the Historic Environment, to explore its more than 320,000 records and 1.3 million catalogue entries for archaeological sites, buildings, industry and maritime heritage across Scotland.

To find out more about what the Heritage Science team does, join us for our event Heritage Science at the Engine Shed on 11 November and read these blogs about their work:

- the fascinating science of stone matching

- a day in the life of a conservation scientist

- gardez l’eau – watch out for the water

- a slate tour of Scotland: shaping historic roofs

- how can we help the historic environment cope with climate change

About the author:

Sarah Hamilton

Sarah Hamilton is a Conservation Scientist with Historic Environment Scotland. She has worked on a wide range of projects relating to the characterisation of traditional building materials and on-site condition monitoring. Sarah has qualifications in Geology, Applied Geology and Architectural Conservation.

View all posts by Sarah Hamilton