Designing for health: architecture in older buildings

Architecture | Written by: Guest | Monday 3 October 2022

The global COVID-19 pandemic has made the dangers of infection an important topic of conversation everywhere. It’s highlighted the importance of both ventilation and sanitation, and restarted the discussion on how architecture can affect health through design.

Lowering CO2 emissions by installing renewable energies and insulating buildings has also got us thinking about how to make sure indoor air remains healthy while adapting traditional (pre-1919) buildings for the future.

Read on to find out how health was historically taken into account in the design of buildings and why it’s now more relevant than ever.

Infection control in historic hospitals

A historic ward in Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, showing large windows on either side. © Survey of Private Collection. Dr G L Malcolm-Smith album. Courtesy of HES.

Before antibiotics, infections could be life-threatening. Over time, doctors and scientists realised that good ventilation and exposure to direct sunlight reduced the rate of infections. Sunlight kills germs and can help people recover from illness quicker. Larger windows in hospitals mean that sunlight floods the room. This also makes the interior a more pleasant place to be for the patients, improving their mental health.

As a result, hospital architects started designing wards based on certain principles, with large spaces, high ceilings and large windows on either side.

This enabled frequent cross ventilation to bring in fresh air. Patients were also rolled onto terraces and balconies to help their recovery in what was called open-air therapy. This was especially common in Sanatoria for treating diseases such as tuberculosis.

Patients were wheeled outside in their beds to benefit from the air and sun. © The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensor: SCRAN

Recent research has proven the theory that fresh air can kill germs through the so-called ‘Open Air Factor’, and that this could also be achieved indoors with a high degree of ventilation.

This is why it was recommended to meet outdoors, or open windows when meeting indoors during the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

Sanitary housing: building healthy homes

Historically, sanitary housing was also considered essential for public health. One early advocate for this was Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson. Suffering from bronchitis and asthma himself, he designed and built tenements in Glasgow specifically with the health of the occupants in mind.

An example of a ‘four-in-a-block’, showing the large windows with traditional sash and case windows.

In the early 20th century, a model of healthy architecture was developed that included the right balance of heating, ventilation and sunlight. Large room spaces and a high wall-to-window ratio are two features which are particularly important. The ‘four-in-a-block’ houses, also known as cottage flats, were built in the 1920s and 30s as part of the ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ campaign and are a successful example of this.

Architects also took advantage of sunlight and, where possible, designed and orientated houses so they could maximise the benefit of the sunlight, particularly in winter.

A cottage in Perthshire, built by businessman and philanthropist A. K. Bell © The Gannochy Trust

In one Perthshire estate, built by Scottish distiller and philanthropist A.K. Bell and managed by the Gannochy Trust, houses on both sides of the streets had living rooms face south-west. This allowed plenty of afternoon light into these rooms.

While not widely used anymore, radiant heat from fireplaces and stoves was also considered healthy. This is a form of heat which heats objects and people directly, rather than heating the surrounding air. This form of heating can have a number of benefits. Radiant heat does not rise, and results in a more uniform temperature. There is evidence that it encourages healing and can help with breathing.

Fires also helped to keep the air dry, which is particularly beneficial in damp Scottish winters. This, of course, had to be balanced with potential health problems arising from smoke. A good draw in the chimney, taking away the smoke, soot and carbon monoxide, was vital.

The traditional building features that help our health

Many traditional buildings have in-built features which take advantage of these design ideas and are still helping to keep occupants healthy today.

Large windows

A row of traditional sash and case windows in an Edinburgh tenement building.

Large windows are an important feature of traditional buildings. The design of the sash and case windows allowed a high degree of ventilation. When opened at both the top and bottom, warmer, stale air can escape through the top part of the sash, while fresh air comes in through the bottom.

It is even better if the house or room has windows on opposite sides as this can help to move fresh air through the building faster. And of course, bigger windows can mean more sunlight streaming into the rooms, generating heat and making spaces brighter.

High ceilings

Along with large windows, higher ceilings and larger rooms are an important characteristic of traditional homes. The larger space can help with air circulation and provide a greater volume of air in a building. With more air available, ventilation can be more effective.

Fireplaces and chimneys

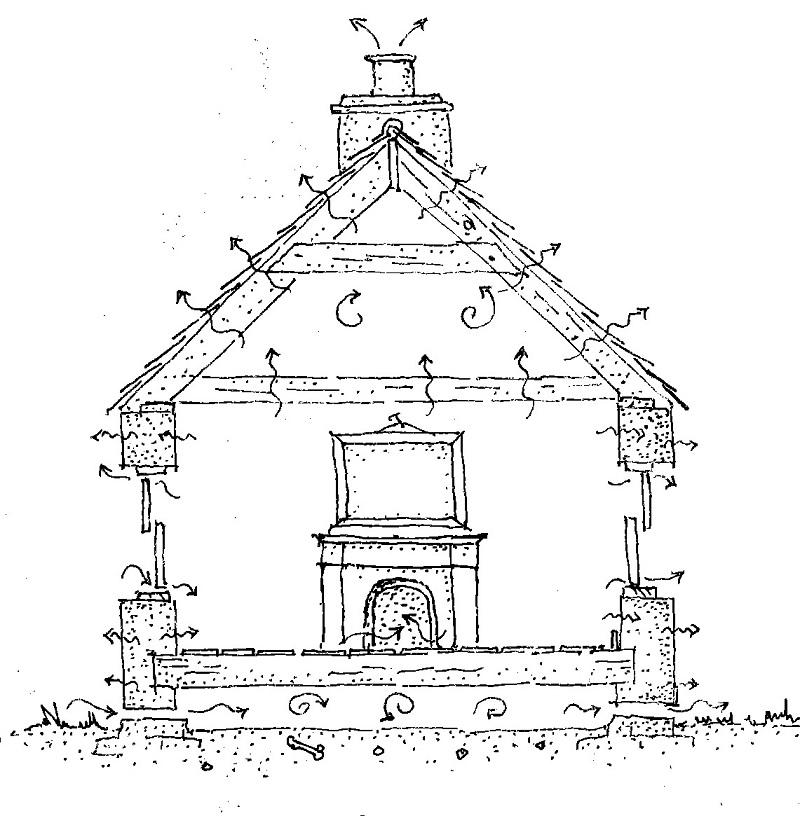

Another important contribution to ventilation rates in traditional buildings are fireplaces and chimneys. Even when unused, stale and warm air can rise up the chimney if it is kept open, drawing in fresh air from the outside at the same time – creating the so called ‘chimney effect’. Draught control can be installed to close off the chimney when necessary.

Fireplaces are not used so much nowadays, but modern alternative radiant heating sources can include radiant heat panels and underfloor heating, which generate a comfortable heat and have similar benefits.

Ventilation is important in a traditional building. The chimney is an important part of drawing stale air up and out.

Planning for energy efficiency and a changing climate

As well as applying age-old design principles of ventilation and sunlight, we also need to consider how retrofitting for energy efficiency can impact these properties. Will a new carpet or wallpaper give off gas when sunlight shines on it? Do some windows need blinds to prevent overheating? Is it a good idea to make your traditional home completely airtight? How can you ensure that there is enough ventilation, but your home is not draughty?

Considerations and pre-planning like this can go a long way to retain the design intentions and maintain the benefits of some of these features, when looking at retrofitting a building. Especially in a changing climate, traditional features can help to keep the environment pleasant.

If you have these traditional features in your home, make sure to use them to ventilate your building and let sunlight come in. And when planning works to improve the energy efficiency of a traditional building, consider how any changes might affect your health.

If you found this interesting, download our recent Technical Paper 36: Architecture and Health to learn more.

To learn more about the energy retrofit of traditional buildings, read our Guide to Energy Retrofit of Traditional Buildings and explore our guidance on energy efficiency in traditional buildings including renewable energy measures.

About the authors:

Anne Schmidt is a Content Officer, working at the Engine Shed. Her background is building conservation and she enjoys telling people about different traditional building materials, particularly lime and sustainable refurbishment. Read more blogs by Anne.

Lila Angelaka is a Senior Technical Officer in the Technical Research Team. Her background is in architecture and conservation, and she previously worked as a Casework Officer. In her current role, she provides technical advice, both internally and externally, and is responsible for the writing and editing of a number of technical publications, such as the Technical Papers and Refurbishment Case Studies. Read more blogs by Lila.

- Share this:

- Share this page on Facebook

- Share on X

About the author:

Guest

From time to time we have guest posts from partners, visitors and friends of the Engine Shed.

View all posts by Guest