Old buildings can’t be energy efficient, right?

Conservation, Sustainability | Written by: Lila Angelaka | Thursday 27 August 2020

Over 20% of Scotland’s houses are traditional buildings (built before 1919). That means one in five of us live in a traditional home!

Some think these older buildings can’t be energy efficient, and that old means cold. Others try to improve the energy efficiency in a building using the wrong skills and materials, making things worse.

But new national energy saving targets came into force in 2019 and we need to improve energy efficiency in our homes. Old buildings must play their part.

Since 2008, Historic Environment Scotland has taken the lead in trialling and demonstrating improvements to historic and traditional buildings through over 30 refurbishment case studies.

In this blog, Senior Technical Officer, Lila, explores some of these projects. Discover how they’ve improved the energy efficiency in older buildings, while preserving their special architectural interest or historic character.

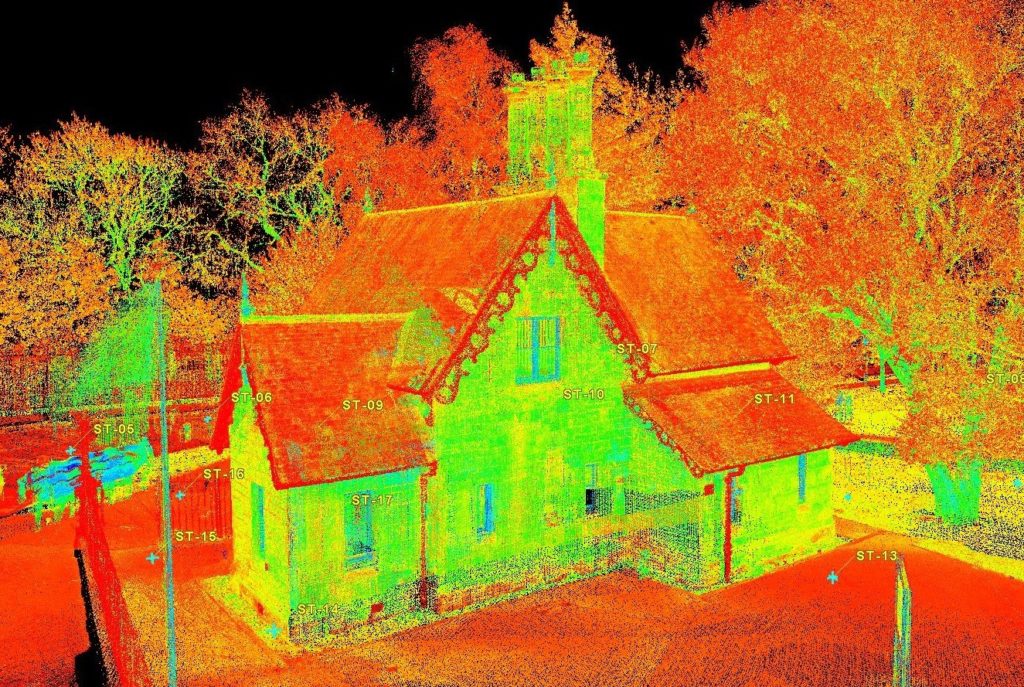

The mid-19th century lodge: Holyrood Park

Holyrood Park Lodge is a Category B-listed, mid-19th century lodge at the entrance to Holyrood Park in Edinburgh. It’s overlooked by the Palace of Holyroodhouse on one side and the Scottish Parliament building on the other.

We retrofitted the lodge to show best practice in energy-efficiency retrofit for traditional buildings, while fitting out the lodge as a shop and interpretation centre. As part of the training and development programme here at the Engine Shed, we’re also using this as an exemplar property for demonstration and teaching.

We carefully chose the most technically appropriate and natural materials, so that they preserved the character and appearance of the listed building. One of our goals was to retain or reinstate original architectural features and traditional finishes which had been lost in previous refurbishments.

We removed 1980s alterations and decoration, reinstated lost fireplaces to the original designs and even used period-style electrical fittings.

To improve energy efficiency, we insulated the building with breathable and natural insulation materials. Wood-fibre insulation was laid underneath the existing timber suspended floors; blown cellulose insulation was installed behind the existing lath and plaster and plasterboard finishes; and wood-fibre board insulation was installed within the roof space and the cooms (sloping ceilings). Existing timber window casements were retrofitted with doubled glazed units and the windows were draught-proofed.

Part of the research work at the Lodge involved long-term monitoring, which examined internal and external conditions of the building, before and after the works. This included temperature, humidity, heat transfer and air-tightness testing, to assess the improvement to the building, in addition to the conservation gain.

We carried out a building energy assessment (EPC) before and after the works. This showed that the works improved the building’s energy performance by 83% (taking it from Band F to upper Band D), without any loss of the building’s historic character!

Explore the full works in Refurbishment Case Study 37

The rare rural home: Downie’s Cottage, Braemar

This mid-19th century Highland cottage is a rare thing indeed! In fact, it’s an exceptionally rare survival of the open-hearth tradition of vernacular buildings in the north east of Scotland.

Traditionally, the heating would have been provided by the two hearths, one on each gable. The roof was originally a heather thatch, but was later covered in corrugated iron, which acted as protection and ensured the survival of the thatch underneath.

Many of early internal fittings were still present, although damaged. The damage included broken flagstones, and detached plaster. Water ingress against the south wall had damaged timber and masonry.

Other external ground conditions and poor drainage had led to settlement of the masonry in some areas and even collapse. To repair this, we rebuilt some of the walls and masonry using salvaged stones and traditional methods.

We also repaired the corrugated iron roof: an important part of the building’s history and significance.

Inside, we insulated the wall using insulated lime plaster, about 50mm thick, which was then limewashed. Underneath the original flagstone floor there is an underfloor heating loop, set in a lime concrete bed and heated by a ground source heat pump. This type of system, where low level heat is delivered into the building fabric for extended periods, is considered suitable for older buildings with a high thermal mass, and the construction of the croft suited this. We also made repairs to windows, timber floors internal linings and fixed furniture.

While modern services have been installed, the cottage’s exterior and interior have remained looking much the same.

The use of renewable energy and the energy efficiency upgrades have ensured that this small building, of proven durability and reliance, has a strong and sustainable future.

Explore the full works in Refurbishment Case Study 22.

The 1920’s ‘garden city’ house: Annat Road, Perth

This single-story detached three-bedroom house was built in the interwar period. Although post-1919, it’s representative of a large number of buildings that are mostly built in a traditional way, but with different aspects, like using more modern materials in their construction. In this case the building has cement-bonded red sandstone on the exterior.

The building was of good build quality and design but the thermal performance wasn’t to modern standards.

On this project we worked with The Gannochy Trust to show technically appropriate thermal upgrades to the building could be made while retaining the design and original feature. Another key part of the project was to show how managing costs and expectations could allow future replication of the project at scale.

In the past, the two chimney stacks had their flues closed. The existing timber windows were double glazed and dated from the 1990s. Luckily, apart from one unit that needed replacement all the timber was in good condition!

Inside, the walls were lined with lath and plaster, with a small cavity between the wall and the lining. The kitchen and the bathroom have solid concrete floors; other spaces have suspended timber floors.

We used wood fibre insulation under the timber floor and in the roof. A new vapour open blown foam was used to insulate the walls – this meant we could keep the original plaster linings. We also used clay paint to manage internal humidity and prevent condensation. In the bathroom, we installed infra-red heating.

The building is now more comfortable for the tenant to live in and is significantly more energy efficient.

This refurbishment was given a Green Apple Environment Award in 2015 and it’s EPC rating was improved from F to E. It saw a 63% improvement in the insulation performance of the solid external wall.

Explore the full works at Annat Road Refurbishment Case Study 20.

Retrofit advice and support

Our case studies show that we can retrofit listed buildings to meet new energy standards. And what’s more, that we can do this in a sensitive and proportionate way. The cultural signifiance and fabric of the building doesn’t need to be negatively impacted!

If you are looking for support and advice on retrofitting traditional buildings:

- explore our free case studies

- read the independent review of our projects

- contact us using TechnicalResearch@hes.scot

About the author:

Lila Angelaka

Lila is a Senior Technical Officer in the Technical Research Team. Her background is in architecture and conservation, and she previously worked as a Casework Officer. In her current role, she provides technical advice, both internally and externally, and is responsible for the writing and editing of a number of technical publications, such as the Technical Papers and Refurbishment Case Studies.

View all posts by Lila Angelaka