Hidden gems in Scotland’s historic gardens

Architecture, Heritage, History | Written by: Jennifer Farquharson | Friday 1 May 2020

Our heritage isn’t just made up of castles and cottages. Gardens, parks, woodlands, and all of our landscapes are just as much part of our past as the buildings built on, in, and around them.

They have a lot to tell us about our social, cultural, and economic history, and today offer sanctuaries for both our wildlife, and our own health and wellbeing.

In this blog, read about three different types of structures you might find in historic gardens and what they tell us about the people who used them.

1. Doocots

Many of us will have bird houses in our back gardens. However, many of them can’t compare to the impressive dovecots, or doocots as they’re known in Scotland, that existed across the country.

Doocots were a dominant part of any garden or landscape belonging to powerful landowners for centuries. The earliest surviving example in Scotland was built in 1576 in the gardens of Mertoun House in Roxburghshire. But they were still built well into the 18th century.

Doocots provided three things: fresh meat, bird droppings, and status.

They could house a vast amount of pigeons. The largest surviving doocot in Scotland, Finavon Doocot, has 2400 nesting boxes. And Corstorphine Dovecot has more than 1,000 nesting boxes. Fully grown pigeons, newly hatched “squabs”, and eggs all fed the house fresh meat. This was especially important during the winter when it couldn’t be procured from other sources.

The droppings from the birds were useful, too. They were collected and used as both an agricultural fertiliser.

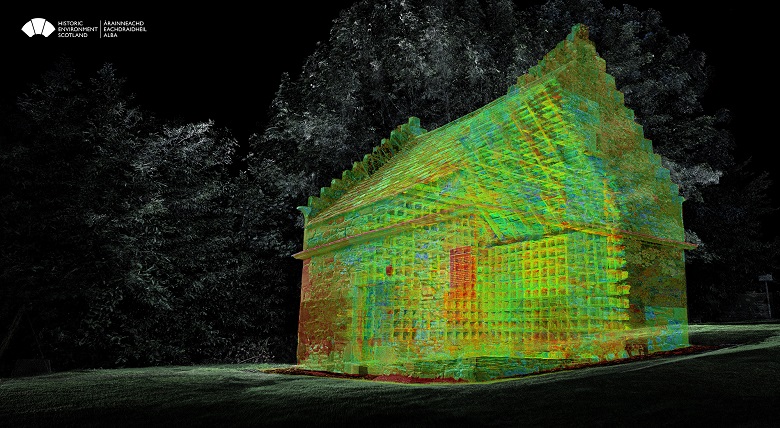

Although functional, doocots could also be highly decorative buildings. Landowners used them as status symbols to show off their wealth. They were built with local materials and each was distinct to the land it was built on and the family who owned it. However, there were two core styles: “beehive” doocots, named for their circular shape, and the “lectern” style, with a steep pitched roof.

Doocots were commonly associated with grand estates and today they are often the only surviving structure left of them. There was a popular belief that if a dovecot was demolished, the laird’s wife would be dead within the year. Could this be why so many survived? It’s not known, today they help us identify where those lost estates might have existed.

They eventually fell out of fashion as the agricultural and meat industries developed and people no longer relied on pigeon. It’s possible that they also caused too many problems with local residents, scavenging on newly sowed seeds on farms.

2. Bee boles

Bees are essential for growing plants and food. However, today their numbers are dwindling and in 2019, a third of bees and other pollinating insects were declining. But did you know bees were as essential for the people of Scotland’s past as they are for us today? In the past, Scotland’s homeowners came up with some inventive ways to provide bees a home. Introducing: the bee bole.

Bee boles are almost completely unique to the UK. The oldest surviving example in the country dates from the 12th century.

The great Scottish weather meant that bees needed some extra protection from the elements. Bee boles offered a solution. Garden walls were built with recesses big enough to fit one or several skeps (straw baskets), offering some shelter from the wind and rain. They were also usually south facing to allow bees to benefit from the most sun. Sometimes they were fitted with locks to prevent theft.

The surviving bee boles, mostly found in Tayside, Fife, and the Lothians, are usually found in ecclesiastical buildings, which had a particular need for candles for religious services, and high status buildings. However, it is likely that rural and lower-status economies also had them, but they simply haven’t survived.

3. Ice houses

You might be enjoying springtime by having a refreshing, cool drink in your garden, straight from the fridge. Although fridges for the home weren’t invented until 1913. So how did people keep things cool before then?

One solution was an ice house. Although they existed in some form centuries ago, used by ancient civilisations including the Romans, ice houses appeared in the UK from around the mid-17th century.

Being built mostly underground helped keep the inside shielded from the sun, and allowed it to benefit from the cool ground. Ice houses were also often built near bodies of water. Not only did this help keep the temperature cool, but this would have offered a steady supply of ice when the water froze over. The ice would then be stored and used to preserve foodstuffs like fish and game.

The largest surviving ice house in the UK is Tugnet Ice House in Spey Bay. It was built in 1830 for packing salmon caught in the River Spey, for sale in London.

If you think you’ve found a bee bole near you, then get in touch with the Bee Boles Register.

You can make the bees in your back garden their own home with the RSPB Give Nature a Home scheme.

To learn more about some the of structures that used to decorate our gardens, take at look at this illustrated catalogue of garden structures from the archives.

Look up the Historic Environment Scotland Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes to discover the landscapes near you.

About the author:

Jennifer Farquharson

Jennifer Farquharson is a Content Officer at the Engine Shed. Jen creates engaging content about our sustainable conservation centre.

View all posts by Jennifer Farquharson