Masons and Merelles: A Pastime of the Past

Conservation, History | Written by: Duncan Ainslie | Wednesday 19 July 2017

Sometime around the 13th century, two masons taking a break from working on Arbroath Abbey might have sat down to a game of Merelles. A large building stone sat between them, crudely carved into a gaming board.

Each man had a set of 9 counters – small stones, wooden beads or pieces of bone maybe. They took it in turns to place or move their set of counters, trying to create a row of three of their own.

Centuries later, in the 1920s, a post-reformation wall was taken down at Arbroath Abbey. It had been built using much older stones and among them, waiting to be discovered, was the masons’ Merelles board.

The history of Merelles

The game Merelles dates back to ancient times. One board was found cut into the roofing slabs at the 1400-1350 BC Temple of Kurna in Egypt, although there is an argument that the board was added later by early Christians. A version of the game using dice is also featured in the 1283 Libro de los Juegos (Book of Games).

Several Merelles boards have been found in Scotland. Another mid-13th century stone board was found during excavations at Jedburgh Abbey in similar circumstances to that at Arbroath while at Dryburgh Abbey a board can be seen carved into the foundation stone of the north wall of the nave.

The Merelles board at Dryburgh Abbey.

Merelles, Merels or Morris?

The name Merelles comes from an old French word merel meaning counter or token. Apparently, the Normans called the game Merels in the 11th Century. Later, the name became adapted again to Morris, and the game became known as Nine-Man’s Morris, which is still sold today.

When playing Merelles, each player starts with 9 coloured counters. They take turns placing them one at a time on the board’s junctions. The aim is to form a “mill”, a row of three counters. Once all of the pieces are in play the players can start moving their counters. They can only move into unoccupied spaces at any adjacent junction. Each time a new mill is formed, the player can remove one of their opponent’s counters. However, counters in mills that have already been formed are safe. Individual counters must be removed first. If there aren’t any individual counters left to remove, players can start to remove counters for their opponent’s mill. If a player is reduced to only having two counters, and therefore can’t form a mill, they lose the game.

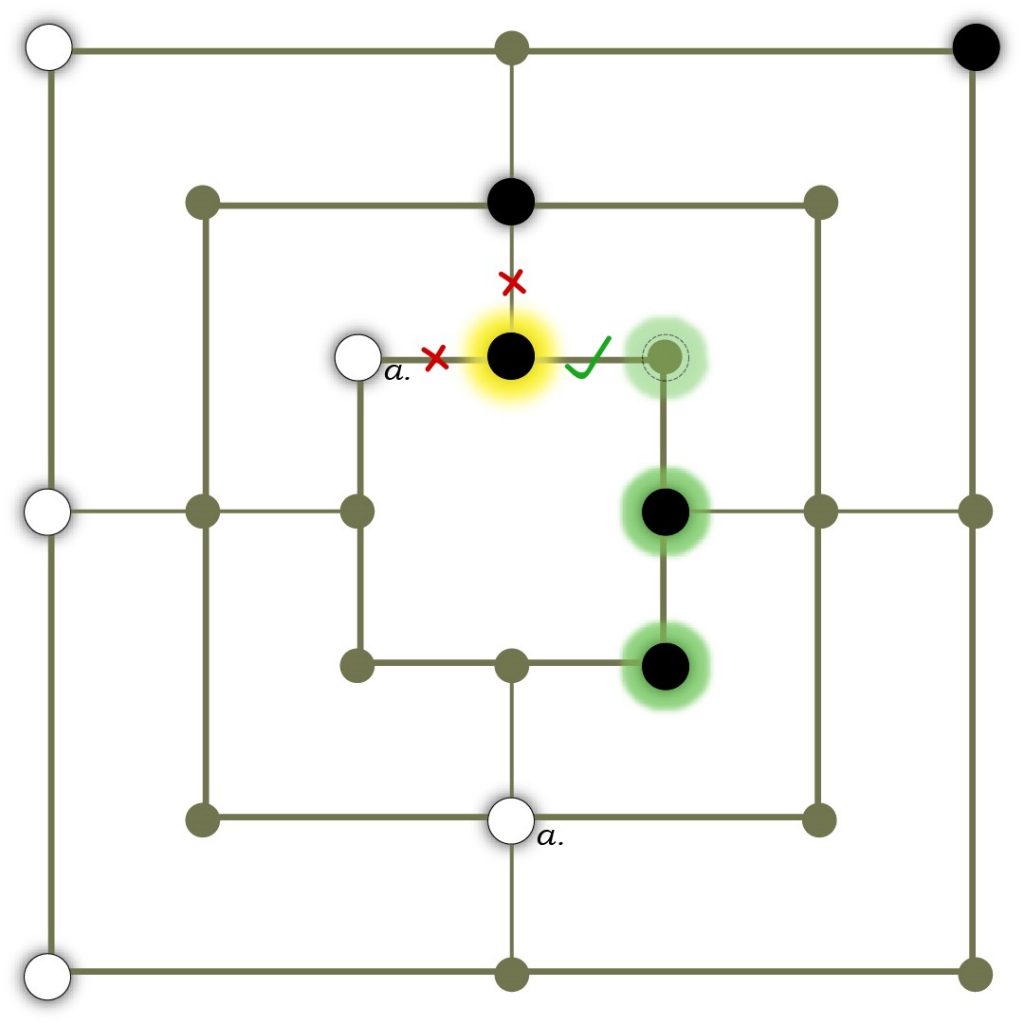

A board showing how to play Merelles.

For example, on the board shown above if the black player wanted to move the counter highlighted yellow, they couldn’t move it upwards or to the left as it’s blocked by the other counters. It can move to the right. Moving to the right would create a mill, highlighted green. The black player can then remove one of the white counters. They could remove either of the individual counters (marked a.) but couldn’t remove any of the three counters on the left hand side because these are safe in a mill.

You can easily make a Merelles board by marking the necessary lines on any surface, perhaps using chalk. Coins or pebbles can be used as counters. Why not try a game yourself?

Learn how to play Merelles with this free activity sheet [PDF, 3.15MB].

About the author:

Duncan Ainslie

Duncan provides support to the Estates team of the Conservation Directorate at Historic Environment Scotland. With a background in history, he enjoys learning about the significance of our properties and the stories we’re able to perpetuate through our conservation work.

View all posts by Duncan Ainslie