Scottish stone makes a clean sweep for Olympic Curling

Heritage, History, Materials | Written by: Madeleine Clark | Tuesday 10 February 2026

The 2026 Olympic Winter Games have started in Italy, and Team GB are already off to a great start with a place in the bronze medal play-offs in the Curling Mixed Doubles! The British Curling team will be hoping to add to their success at the 2022 Olympics, where they achieved a Gold medal for the women’s team and a Silver for the men.

But before 2026 medals are even announced – Scotland has a material that ranks higher than gold for one of these games. There is only one quarry in the world that makes all the curling stones used in the Winter Olympics, and it is in Scotland. In this blog, I delve into the history of curling and the mighty Scottish stone that is the primary focus of this sport.

What is curling?

Curling is a skilful game played on ice. Two teams alternate sliding their eight curling stones across the ice, with the aim of getting as close as possible to the centre of the target (known as the House). Two sweepers can help to direct the stone and increase the distance travelled by applying friction to the ice ahead of the stone with brooms or brushes. The name derives from the rotation of the stone as it is released, causing it to curl along the ice towards the target.

Photograph of Lady Henrietta Gilmour (in black) and team curling at Montrave, Fife in 1896 © Scottish Life Archive. Courtesy of HES

Scottish curling origins

Curling, in some shape or form, has been a part of Scottish sporting life since at least the 16th century, when winter conditions reliably froze lochs and bodies of water solid enough to be used for the game. Stirling’s Smith Art Gallery and Museum is home to the world’s earliest known curling stone, dated to 1511, and found in the Milton Bog. It is easy to speculate that the stone lay buried there for centuries after falling through the ice during a game.

There has been some debate about the origins of curling, with some suggestion that the Low Countries may also have a claim to the game. However, records indicate that if the game did not originate in Scotland, it was certainly played here very early on in its development.

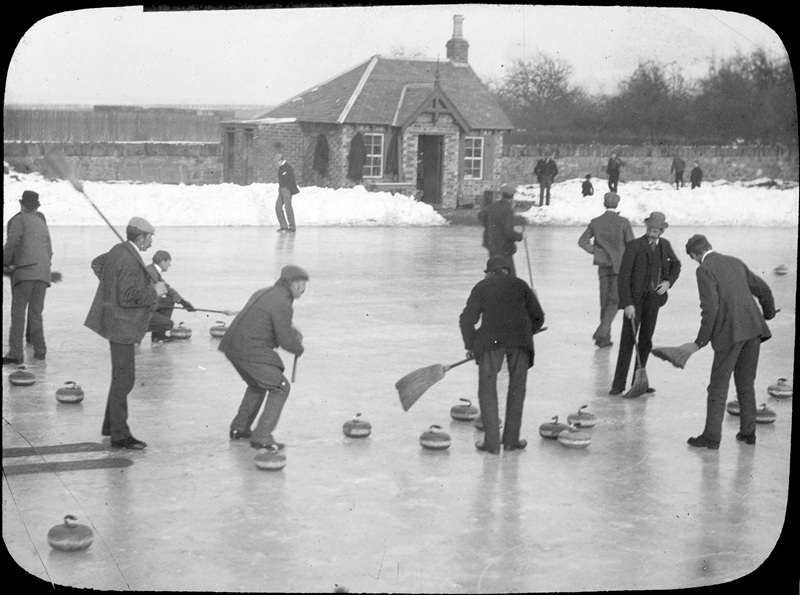

Curlers in the middle of a game at Dalkeith, Mid Lothian, c. 1900 © Scottish Life Archive. Courtesy of HES

Curling in Scotland today

The “Little Ice Age” that once brought ideal ice conditions for curling is long gone and the sport has mainly moved indoors in Scotland. The first indoor rinks opened at the start of the 20th century and there are 21 indoor rinks spread across Scotland today.

The Royal Caledonian Curling Club retains a standing rule for a ‘Grand Match’, between North and South Scotland, ready to be played outside whenever the ice is deemed thick enough – although this hasn’t happened since 1979. Wherever it is played, the Scottish landscape continues to provide one of the most important elements for the game: the curling stones.

Local Kinross curlers on a frozen Loch Leven on Boxing Day in 2010 © Hazel Saunderson

Where curling stones come from

Ailsa Craig is a small, uninhabited islet on the Ayrshire coast, but it is from here that all of the Olympic curling stones are sourced. These curling stones require two types of microgranite, both of which are found on the island; Ailsa Craig Common Green and Ailsa Craig Blue Hone.

Aisla Craig in Ayrshire © Kays Scotland

The Building Stone Database for Scotland provides more information on the wider formation. While Ailsa Craig is well known for its curling stones, it is also found in other uses around Scotland, so keep an eye out and you might spot it, for example, on the setts in Glasgow City centre or The National War Memorial in Edinburgh (Ailsa Craig, GeoGuide).

There is only one firm with permission to extract the granite, with a contract running until 2050, and that is the Kays, who have been producing curling stones since 1851. The extraction of the stone is very well regulated, with strict limits as to how much can be removed each year. The masons also have to be very careful when and how they work on the island, as it doubles as a bird sanctuary with diverse flocks of birds that inhabit the site.

Kays only harvest boulders from the island every few years, and they produce approximately 2000 curling stones a year, each weighing around 20kg. They described the process to us:

“The boulders tend to fall naturally from the cliff face. Ideally, we are looking for a boulder over 4 tonnes and without surface flaws. Once located the boulders are brought from the quarry to the lighthouse area on the island and then brought back to Girvan by boat where they are stored until needed.”

© Kays Scotland

We asked them what makes Ailsa Craig’s granites so suitable for curling stones, and why they are so highly regarded:

“The Ailsa Craig granite has proven itself over 170 years. The Common Green Granite which makes up the body of the stone is tough and has a naturally elasticity which allows the stones to spring in contact when they collide on the ice. The striking band (the contact point when the stones collide) tends not to chip easily and the stones will last a long time if properly looked after. The Blue Hone running edge which runs along the ice…does not absorb water, and it is perfect for running along the surface of the ice. Together the two types of Ailsa Craig granite make for a perfect curling stone.”

© Kays Scotland

Researching the geology of curling stones

Minerologist and competitive curler, Derek Leung, conducted research into the geology of curling stones, and he detailed the reason why there is this difference in performance between the two types of microgranite used:

“The main distinction between running bands and striking bands lies in grain size: Ailsa Craig Blue Hone is equigranular (a rock comprised of fairly equal-sized mineral grains), apart from sparse phenocrysts (larger, conspicuous crystals present in the rock). Whereas …[Ailsa Craig Common Green has] a larger grain-size distribution and a greater proportion of larger (millimetre-sized) minerals.”

This combination is required because, as this research (and Kays’s experience) demonstrates, the Blue Hone can chip when striking other stones, so would be unsuitable for use on the full body of the stone. However, it provides a great running surface as its smaller mineral grains makes it less likely to pit and distort the surface than the Common Green. It is also this running surface that provides the curl that is so essential to the game. If you look at the bottom of an Ailsa Craig curling stone, you will be able to see the difference in colour of the inset Blue Hone.

We asked Kays how they know which boulders will provide the best stones:

“Sourcing the material is mainly done by eye. We are lucky in that everything comes from Ailsa Craig which has so far provided us with quality granite for our purposes. We discard obviously flawed boulders, but we never know what we will find when a boulder is cored out, that’s down to geology and nature.”

Watch their short film on making Olympic Curling Stones.

How curling stones are made

While some of the machinery has been updated since the 1850s, the skills needed to make the stones have continued to be passed down. A lot of the processes are done manually by masons, and even the mechanised elements require skilled supervision. There is currently a team of 16 people at Kays, ranging from apprentices who are learning their skills on the job, up to those with more than 30 years of experience.

Paul from Kays told us, “We try to ensure that each team member learns each step of the process but the most specialist part of the process is, without doubt, the back end polishing which is a true skill. It is this polishing that makes our curling stones stand out in the curling world.”

© Kays Scotland

The team have been especially busy to make sure all the curling stones are ready in time for the 2026 Olympics, but they have had over 100 years of practice, as they first produced stones for the Olympics in Chamonix in 1924. They told us: “This will be our eighth Winter Games. All our stones are produced to the highest standard, but it is fair to say the Olympic stones are given just a little bit more scrutiny!”

The Ailsa Craig granite formation really puts Scotland on the global stage when it comes to the Winter Olympics curling – along with the quality of our players, of course. While we do not yet know the outcome of the competition, it is great to know that whatever happens we can count on a Scottish presence in the finals!

If you are interested in giving curling a go, find out more about curling and where you can play.

Update your personalised ad preferences to view content

About the author:

Madeleine Clark

Madeleine Clark is a Technical Officer in the Technical Conservation Team. Her main focus is providing technical advice, particularly on Retrofit, but she also has a keen interest in traditional materials and skills.

View all posts by Madeleine Clark