Poetry from concrete: Scotland’s fascinating historic concrete and brutalist architecture

Architecture, Conservation, Materials | Written by: Jennifer Farquharson | Tuesday 16 December 2025

Historic building conservation is for buildings more modern than you might expect.

When you picture historic places, you may imagine Neolithic settlements like Jarlshof. Or abbeys like Inchcolm, medieval cathedrals like Glasgow, Renaissance palaces like Linlithgow, and even Victorian tenements.

What probably does not come to mind are our early concrete buildings or 20th century Modernist and Brutalist architecture (like the recently saved Bernat Klein Studio), but these are also an important part of our built heritage.

Let’s start with some definitions

- Cement is a fine powder used as a binding agent in concrete

- Concrete is a composite material made from a mixture of cement, water, aggregates (like sand and gravel), and sometimes additives

- Mass concrete is a large volume of concrete, such as in a dam or bridge foundation, where special measures are needed to manage the heat produced during the hardening process and prevent cracking

- No fines concrete is made by omitting fine aggregates (hence ‘no fines’)

- Precast concrete consists of concrete elements poured and formed off site, e.g. concrete blocks

- Reinforced concrete combines concrete with steel bars or mesh to provide tensile strength, making it useful for structural elements like beams and columns that experience tension

View of the Glenfinnan Railway Viaduct over River Finnan, west Highlands. Built in 1901, with 21 arches, it is the longest concrete viaduct in Scotland.

A brief history of concrete

Concrete pre-dates the Romans, but they took it to new heights. Concrete was used in Roman times in a hydraulic cement concrete (a mix of lime putty and pozzolana). It is not to be confused with Roman cement, however—a quite different material, patented by James Parker in 1796.

Roman concrete was used structurally and as a filling within masonry and brick walls. As a building material, concrete was lost until a revival during the Middle Ages. At this time, and until the mid-to-late 19th century, it was made using lime.

Modern concrete (using Portland cement) was patented in 1824 by Joseph Aspdin, and was first used as mass concrete mostly in foundations, harbours, bridges and floors, as it was particularly useful for its strength and ‘setting capabilities’ – meaning that unlike lime mortar, once it was poured, it could be left to set for a week with little to no intervention required.

One of the foundations or ‘caissons’ for the Forth Bridge, at the construction yard in South Queensferry in 1885. The caissons formed platforms upon which the rest of the railway bridge would stand. They were filled with concrete until they sank to the seabed, then fixed down. © National Museums Scotland.

As a structural material, early concrete had a low tensile strength (the stress a material can withstand before it fractures). This led to the development of reinforced concrete in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries to create a more versatile material which could be used in a range of buildings and structures.

Mass concrete

The 1869 Waverley Hotel in Melrose is possibly the earliest example of a mass concrete “building” in Scotland. There is an earlier example of its use at Tugnet Ice Houses in Moray, circa 1830. Structures around Morvern on the west coast used ‘no fines’ (meaning it omits fine aggregates) mass concrete from 1871 to 1906. In 1909, mass concrete was used to build the ½ mile wide Blackwater dam at Kinlochleven. It was also commonly used for houses in Shetland from around 1900 into the 1930s.

Tugnet Ice Houses and Fishing Station, Moray. Built circa 1830, the long east elevation with louvered vents (ice chuts) is an early example of shuttered mass concrete.

Modernism

Concrete, reaching its modern form by the 1920s, provided opportunities for the Modernist movement in architecture. After the elaborate decoration of Victorian architecture, Modernism focused on the function of a building. Rejecting ornamentation, it emphasized clean lines, geometric shapes, and open floor plans utilizing modern materials like steel, glass, and concrete.

Bernat Klein Design Studio, Scottish Borders. Built in 1972 for the textile designer and artist Bernat Klein to designs by architect Peter Womersley. Purchased in a dilapidated state in July 2025, significant efforts are now underway to look at the building’s full restoration to a design studio.

The Weir Administration building in Cathcart was an example of patented early reinforcement building systems (for commercial use). The design was purchased from Albert Kahn’s Trussed Concrete Steel Co. in the USA, using their steel truss system for the building’s structure and it allowed for more open-plan spaces—an innovative build for 1912.

Pillbox near Devil’s Elbow, Glenshee, Perth and Kinross. Constructed in 1940-1941 from granite blocks and concrete and set into the slope. The pillbox was part of the Cowie Line, a Second World War strategic anti-invasion obstacle.

Art Deco

The India of Inchinnan tyre factory near Paisley (built around 1929-1930) is a great example of Art Deco buildings which sometimes used concrete in their construction. Others include Aberdeen’s Bon Accord Baths and Paisley’s Hawkhead Hospital. For more on this period, you can explore our publication Art Deco Scotland: Design and Architecture in the Jazz Age by Professor Bruce Peter.

India of Inchinnan tyre factory (former), Renfrewshire, built 1929-1930, showing its main entranceway.

Brutalism

A later offshoot of Modernism was the post-war Brutalist architecture of the 1950s. It showcased bare building materials and used angular lines, geometric patterns, and a monochrome colour palette.

Because of its minimalist approach, lots of public service buildings were constructed in the Brutalist style: libraries, judicial buildings, universities, and low-cost social housing.

Cables Wynd House (aka Leith Banana Flats), Edinburgh. Built between 1962–1965 and designed by Alison & Hutchinson & Partners under the leadership of Robert Forbes Hutchinson.

Castle Terrace Car Park in Edinburgh, completed in 1966 in the Brutalist style was Scotland’s first multistorey car park and became a Listed Building in 2019. The Centre in Cumbernauld, designed in the 1950s and built well into the 1960s, was a massive multipurpose recreation building, featuring shops, accommodation, an ice rink, bowling alley, health centre, police, ambulance and fire stations, and eventually a library and technical college. You can view a series of illustrations of Cumbernauld Town Centre by Michael Evans on trove.scot.

Other notable examples in Scotland include St Peter’s Seminary in Cardross and Cables Wynd House (aka Leith Banana Flats) in Edinburgh. Interestingly, the Bernat Klein Studio in the Scottish Borders is considered late Modernist with Brutalist influences.

Common problems in concrete buildings

Some issues appear cosmetic, but they may be a sign of potential deeper moisture problems.

Early aggregates, which were typically locally sourced – such as marine aggregates, had high concentrations of salts. When a process called efflorescence occurs, these salts are drawn through the concrete by the movement of moisture. When the moisture evaporates, salt deposits are left on the surface of the concrete or clog its pores, trapping moisture inside.

In addition, if too much water is used when mixing concrete, or any other mortar, this creates a porous, weaker material which lets in more moisture and pollutants from the air. Environmental impacts like air pollutants and acidic soils can cause surface disintegration over time. Chloride salts, which are found in water (especially saltwater) pose a big risk, as they penetrate deeply, break up structures and corrode reinforcements in concrete structures like metals – it’s best to use fresh water when mixing.

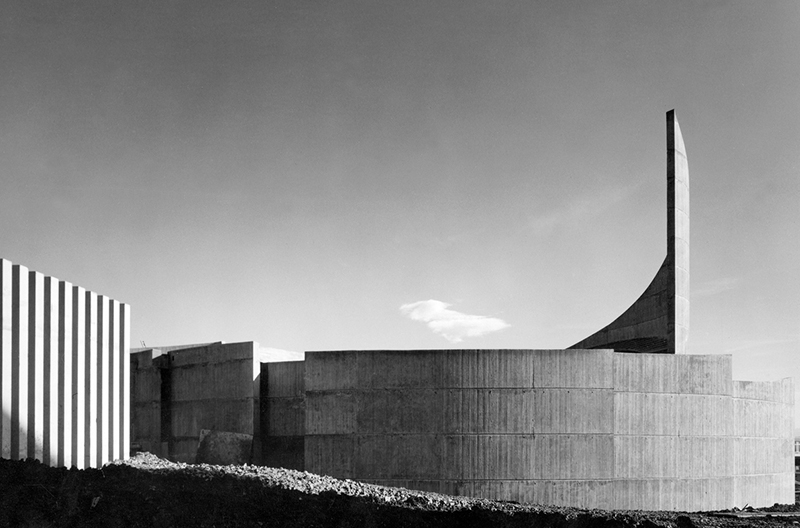

St Andrew’s Roman Catholic Church, Livingston, designed by George R M Kennedy for Alison & Hutchison & Partners in 1968, completed 1970. © Courtesy of HES (Kennedy, GRM and Partners)

Corrosion of reinforcement can also be a significant problem in early structures – moisture management is key. Infrastructure like bridges also bear a lot of weight and stress, which can pose a risk to their condition. This sustained stress causes ‘creep’, which reduces the compression zone of columns, slabs and beams, and may cause cracking.

The former John Lewis plc (previously Norco House) George Street, Aberdeen was built in 1966-1970 by Covell, Matthews and Partners.

Conserving concrete buildings

Concrete buildings are a significant part of our built heritage and include some of our most pioneering engineering, innovative use of materials, distinct construction techniques, and artistic and architectural movements like Modernism and Brutalism. Careful thought must go into their conservation by the people who manage and look after them, in order to conserve this part of our heritage and give them a new lease of life.

Gala Fairydean Rovers Football Club Stadium, Galashiels. Designed by architect Peter Womersley and officially opened in 1964.

If you want to learn more about historic concrete, or specifying repair and conservation works, get our Short Guide 5: Historic Concrete in Scotland parts 1-3.

Or, for the history buffs among you, explore this 1877 publication, Concrete: its Use in Building, by Thomas Potter, Clerk of Works to Lord Ashburton

About the author:

Jennifer Farquharson

Jennifer Farquharson is a Content Officer at the Engine Shed. Jen creates engaging content about our sustainable conservation centre.

View all posts by Jennifer Farquharson