4 Key Takeaways from Our 2024 Lime Finishes Summit

Conservation, Materials, Skills | Written by: Anne Hitchman | Monday 30 September 2024

Lime has been used for a variety of different purposes in buildings for thousands of years. This includes lime for pointing, as well as surface finishes including renders, harls, and limewash applied to buildings throughout the UK. Thanks to recent research, we are re-discovering some of these historic applications, and learning how we can use lime in the modern world.

Discover four key takeaways about this from our ‘What’s the Point?’ lime finishes summit.

More than 300 people joined our 2024 lime summit, with over half joining online.

1. A great number of buildings had surface coverings historically

Evidence from a number of our conference speakers shows that buildings were historically often covered with lime. This was true throughout Scotland and the UK and evidence is sometimes found in the most surprising ways.

Dr Tim Meek, Post-Doc researcher at the University of Stirling, showed us drawings of buildings in historic Edinburgh that were once covered with lime finishes, including Edinburgh Castle. Photos from the late 18th century showed us that there was evidence of this until relatively recently.

306-310 Lawnmarket, Edinburgh from around 1890 showing a façade with a lime finish. © Courtesy of HES (William Notman Collection).

Corey Lane, Conservation Building Surveyor and lecturer, gave similar evidence for timber-framed buildings. Rather than the characteristic black and white you see today, lime would have covered the timber work. This would have the additional benefit of protecting the façade, particularly the more vulnerable areas between the timber and the infilled panels.

Nicola Dyer from English Heritage talked about stone buildings in and around Bourton-on-the-Water in the Cotswolds. She presented many examples of flakes of limewash still adhering to the stone buildings even today. Historic photos show the same buildings covered with limewash.

Moving into the North Yorkshire National Park, Vicky Flintoff from English Heritage examined the tooling marks of stone buildings there. She explained that tooling marks were historically added to ensure that the surface finishes stick to the stone better. Older examples were often rough and uneven, since they were covered anyway. It is only more recently that fine and regular tooling marks were created as an aesthetic choice, meant to be seen.

Looking at historic examples in Scotland, Dr Callum Graham from Historic Environment Scotland (HES) showed that in some cases the surface finishes were applied while the wall was being built. There was no separation between the building mortar and the surface finishes. He hypothesised that this would have created the ideal condition for curing these mortars.

Moving to India, Vrinda Jariwala, PhD researcher at University of Oxford, presented the fascinating technique called Araarish. This is a fine lime finishing technique polished with coconut oil to produce a beautifully shiny and water resistant surface. It was used historically in many palace interiors in India.

2. Covering buildings protects them against water ingress, especially in a changing climate

Historic lime finishes were not all about aesthetics, but also had a practical purpose. They helped to protect the façade and any weak joints between two materials. This becomes increasingly important today, where climate change is leading to wetter and more extreme weather.

Dr Robyn Pender, Weathergauge Ltd, gave the scientific basis for this by showing how water gets sucked through the thin capillary pores in a mortar. This helps to move water out of a wall and towards the surface where it can then evaporate. She also presented a case study of a damp church tower, which dried out after a lime finish was applied to the outside. This supported Tim’s research of simulating storm conditions on a wall with and without surface finish. The wall with the finish was much better at keeping the water out.

Roger Curtis, HES, considered that conservation and heritage is now often understood as preserving the romanticised image of buildings with bare masonry. This image began in the 19th century and does not represent a building’s entire history or original appearance. Stirling Castle and nearby Cowane’s Hospital are examples of the reversal of this. Here, the surface finishes give better protection for the walls, and could be a pragmatic approach to the increasing rainfall.

Cowane’s Hospital, Stirling with a newly applied harl coat. © Roger Curtis.

3. It is important to retain the skills for these traditional materials

Passing on the skills associated with these materials is vital to preserve this important part of our tradition. Only by ensuring that the appropriate training is available can we pass this on to future generations.

Looking back, Dr Gerard Lynch, bricklayer and lecturer showed many examples of different historic pointing styles which used to be taught as part of the bricklaying profession. However, since they are not used very frequently today, there is a danger that these skills will be lost.

Niharika Pareek, MSc student at the University of Edinburgh, gave an example of how these traditional skills are passed on in Jodhpur, India. A great example of a continued tradition, the skills around lime are passed down through the generations. Repair is a community activity, and many people are aware of these skills from childhood, as part of everyday life.

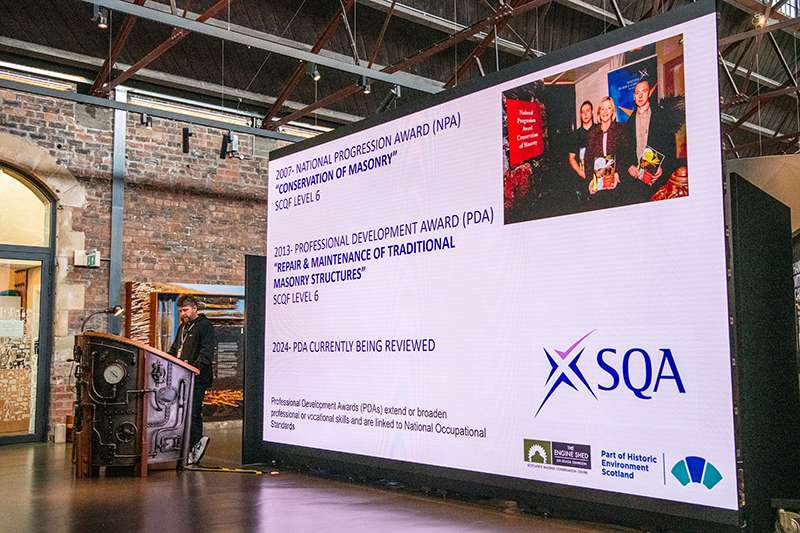

The importance of these skills is recognised by the industry, as Charles Jones, HES presented. Changes and updates to the curriculum of lime-related craft qualifications are expanding and re-introducing relevant units. This will help to ensure the future craftspeople have a better understanding of the material and its traditions.

Charles Jones presenting on the different SQA qualifications relevant to the discussions around lime.

4. Cooperation between all people involved in a building project is vital

Finally, there were a number of interesting case studies, where cooperation between all the construction disciplines made all the difference.

Tara Crooke from National Trust for Scotland talked about the phased approach for Falkland Palace repair. Here, different tasks were carried out at the same time to be able to share the scaffold. This included masonry repairs using lime mortars, consolidation of statues and waterspouts, as well as conservation of the heraldic emblems above the door. It was also important to allow visitors and residents continued access to the site.

Bryan Dicks, National Trust for Scotland and Natasha Huq, Groves Raines Architects Studios, presented about a range of complex repairs to Preston Tower. This showed a variation of decay at different height, requiring individualised repair strategies. Due to the complex repairs necessary, various disciplines worked together to come up with the most appropriate repair solution and materials.

Find out more about historic external lime finishes

It was an inspirational day, with so many examples of lime in use. To find out more about this, read our recent blog ‘What do historic lime finishes look like on Scottish traditional buildings?’. To delve deeper into the research around this subject, read Technical Paper 31: Historic External Lime Finishes and Technical Paper 33: Masonry Pointing and Joint Finishing. Both publications have gazetteers of examples with different finishes.

The speakers of the event were:

- Dr Tim Meek, Post-doc at the University of Stirling

- Dr Robyn Pender, Director of Weathergauge Ltd

- Corey Lane, Conservation Building Surveyor and Lecturer at Birmingham City University’s School of Architecture

- Niharika Pareek, MSc student of Conservation Architecture at the University of Edinburgh

- Nicola Dyer, Properties Curator at English Heritage

- Charles Jones, Technical Conservation Skills Program Manager at Historic Environment Scotland

- Dr Gerard Lynch, Bricklayer and lecturer

- Vrinda Jariwala, PhD researcher at the University of Oxford

- Dr Callum Graham, Conservation Scientist at Historic Environment Scotland

- Vicky Flintoff, Building Maintenance Officer at Historic England

- Natasha Hug, architect at Groves Raines Architects Studios

- Bryan Dickson, Head of Building Conservation Policy for the National Trust for Scotland

- Tara Crooke, Lead Conservation Surveyor for the National Trust for Scotland

- Roger Curtis, Acting Director of Operations at Historic Environment Scotland

About the author:

Anne Hitchman

Anne Hitchman is a Content Officer, working at the Engine Shed. Her background is building conservation and she enjoys telling people about different traditional building materials, particularly lime and sustainable refurbishment.

View all posts by Anne Hitchman