5 things you might not know about Robert Stevenson

Architecture, History | Written by: Phoenix Archer | Thursday 6 August 2020

Many of us have seen the work of Scottish civil engineer Robert Stevenson with our own eyes, perhaps without realising it.

Stevenson was famous for designing and building many of Scotland’s lighthouses for the Northern Lighthouse Board between 1794 and 1833.

In this blog, discover some things about the famous engineer you might not have known.

He was born into a family that tried to make its fortune from slavery

Advances in technology and industry led to the creation of the modern lighthouses Robert Stevenson helped design and build. There was more commercial and industrial demand for sea travel, and greater engineering knowledge made it easier and faster.

Scottish traders were among those capitalising on those advances. However, there was an appalling side to their profit. Scotland’s wealth was built on the exploitation of enslaved people.

Stevenson’s father, Alan, and his uncle Hugh ran a trading company that dealt with goods grown by slaves in the West Indies. These goods included sugar and tobacco. Much of the family’s early wealth came from merchants doing business in the Caribbean.

Alan and Hugh died when Stevenson was very young of fever, a common risk in the West Indies.

After his father’s death, his widowed mother, Jane, and two-year old Robert were left in a condition of great want. This was despite Jane’s private schooling and having a brother-in-law who founded Laurieston district in Glasgow’s Gorbals.

He built his first lighthouse at aged just 19

When Stevenson was around 20, his mother married Thomas Smith, the first engineer for the Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB). Jane’s marriage to Smith took longer than expected because she had to trace and divorce her second husband, who abandoned her.

After spending time with Smith working on lighthouses, Stevenson fell in love with engineering. Smith encouraged this and Stevenson went on to study at a technical school. At 19 years old he supervised the construction of a lighthouse on the island of Little Cumbrae in the Firth of Clyde.

He worked as an apprentice for five years and became a fully-fledged lighthouse engineer at 26. Smith hired him as a superintendent for the Northern Lighthouse Board which constructed Scotland’s first lighthouses after the 1786 Act.

Stevenson became NLB’s sole engineer in 1808.

He enjoyed collaborating with others

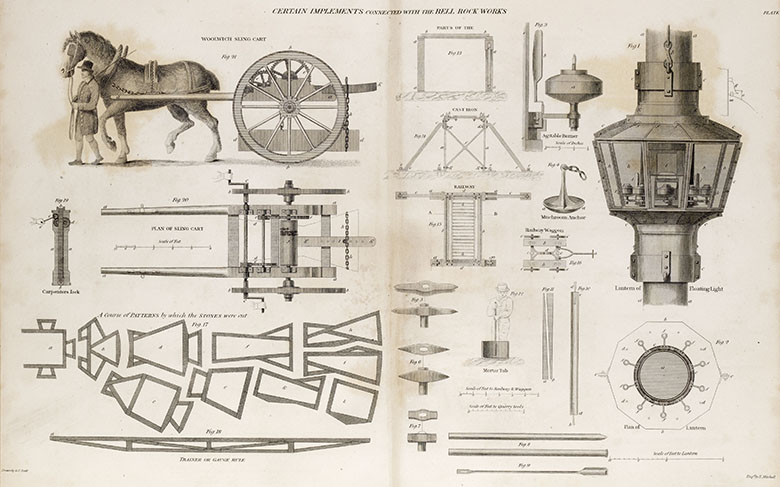

Stevenson was a key figure on one of the most challenging builds of early Scottish lighthouses: Bell Rock.

The lighthouse was a feat of engineering in itself. It was built into a sandstone reef and the North Sea created hazardous, limiting, and difficult working conditions.

Even so, Stevenson introduced a system of seven rotating oil lamps, placed in front of parabolic silver-plated reflectors. Bell Rock was the first lighthouse to use red and white flashing lights, as Stevenson adapted the work of Captain Joseph Huddart. Stevenson’s own account of building the Bell Rock can be read online today.

Although Stevenson is often given sole credit for Bell Rock, the chief engineer of the build, John Rennie, and the foreman, Francis Watt, were also key contributors.

Rennie introduced a more gradual slope than John Smeaton’s design for Eddystone Lighthouse, which was a major step forward for lighthouse design. This helped the building cope with the violent conditions of the North Sea.

Watt also developed the iron balance crane, which became a key tool in lighthouse builds and was the forerunner of the modern tower crane.

His family had some well-known names…

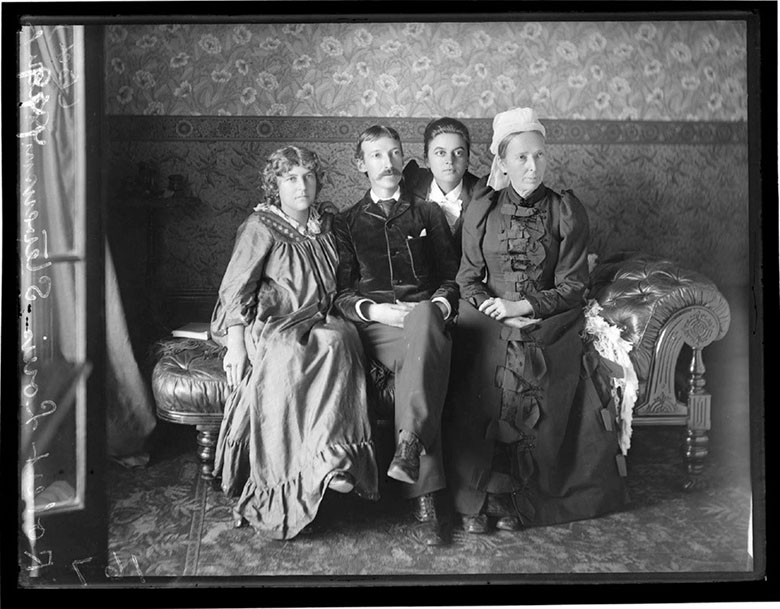

Image c/o: State Library of New South Wales / Public domain

Stevenson had three sons with his wife (and stepsister) Jean Smith: David, Alan, and Thomas. They all became lighthouse engineers as did David’s sons Charles and David Alan. Together, they became known as the Stevenson Engineers. The six of them, along with Thomas Smith, built over 150 lighthouses in Scotland.

© Courtesy of HES

These included the tallest Scottish lighthouse at Skerryvore (1844), the most westerly lighthouse at Ardnamurchan (1849), and the most northerly lighthouse Muckle Flugga, off Unst, Shetland (1854).

A more well-known name might be the son of Thomas Stevenson, and one of Robert Stevenson’s grandsons. Robert Louis Stevenson was born in 1850.

His early education focused on engineering, but he broke with tradition and instead focused his efforts on writing. Some of his best-known works include The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Treasure Island, which he started writing when visiting Braemar in 1881.

He wasn’t just known for lighthouses

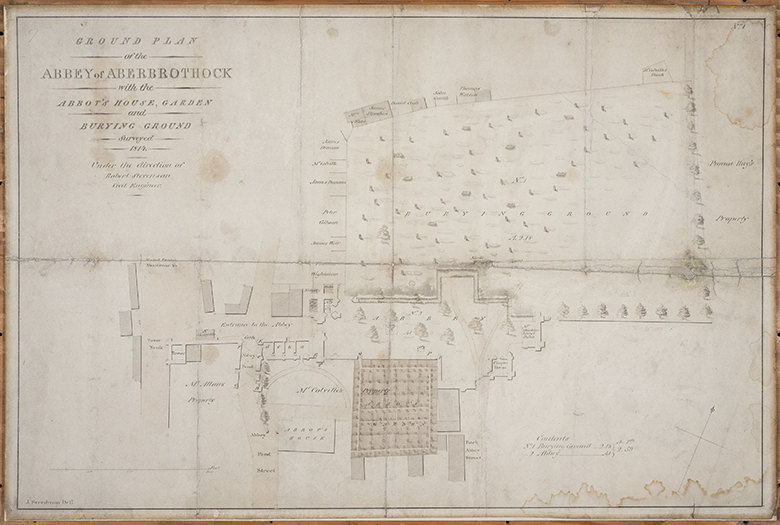

© Crown Copyright HES

Although Stevenson was a skilled engineer who specialised in lighthouse design, his work garnered him a reputation that made his advice highly sought after.

He consulted on building projects including Regent Bridge (1814), and Melville Monument (1821) in Edinburgh. The Melville Monument, dedicated to 1st Viscount Melville Henry Dundas, is so tall, they called Robert in to advise on the project to reassure local residents. Today, controversy around the statue centres around the unsavoury side of Dundas’s legacy. Dundas used his influence to delay the abolition of the slave trade by 15 years.

Stevenson also branched out on other builds, but knew his talents remained with maritime engineering. He designed bridges including Marykirk Bridge in between Angus and Kincardineshire (1814), Annan Bridge in Dumfriesshire (1827), and Stirling New Bridge (1831).

With his sons, Stevenson improved navigation in the River Tay (1834 – 1842). They dredged streams, removed fords and deepened and widened the channel between Perth and Newburgh. He also designed a curved sea wall at Trinity in Edinburgh (1821), part of which is still in use today.

Explore Scotland’s coasts

Most of Scotland borders the sea, its coast a ribbon more than 10,000 miles long that defines our enduring relationship with the oceans. Discover more about Scotland’s coasts with this online exhibition.

Explore a timeline of Stevenson’s achievements in the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame.

Find out more about the impact climate change is having on Scotland’s coastal heritage in the Guide to Climate Change Impacts.

About the author:

Phoenix Archer

Phoenix Archer was a Next Step Initiative trainee based at the Engine Shed in 2019/2020. She hails from Jamaica and Yorkshire in England and graduated in Celtic Studies at the University of Aberdeen. One of her favourite things to do is finding out interesting information about heritage, culture and the arts.

View all posts by Phoenix Archer